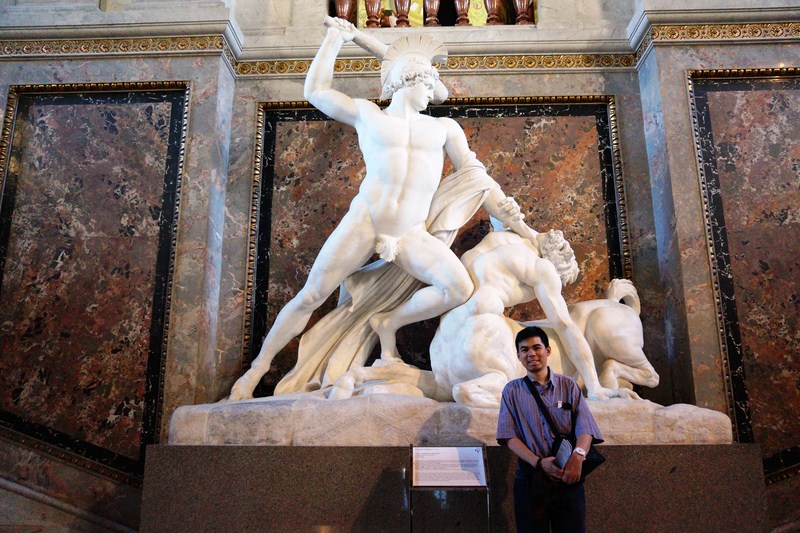

The Kunstkammer Wien, the most important collection of its kind in the world, has 2,162 fabulous artworks passionately collected by the Habsburg emperors (above all Rudolf II) and archdukes over centuries.

Check out “Kunsthistorisches Museum“

One of the most important chambers of art and wonders in the world, it was opened to the public on March 1, 2013 after years of extensive refurbishment (between 2002 and 2012).

This “museum within the museum” has 20 galleries which fills the lower eastern wing of the main building of the museum. On an area of 2,717 sq. m., more than 1,000 years of history can be experienced in the Kunstkammer.

A Carolingian ivory tablet from the 9th century is the oldest exhibit while a ceiling painting, from the year 1891, is the youngest.

The Kunstkammer, aside from showcasing the standout items of various Habsburg collections put together from the 16th century onwards, also demonstrated the best of nature and man’s creative abilities.

The encyclopedic and universal collections of the Kunst-und Wunderkammern (arts and natural wonders rooms) from the late Middle Ages to the Renaissance and Baroque periods attempted to reflect the entire knowledge of the day.

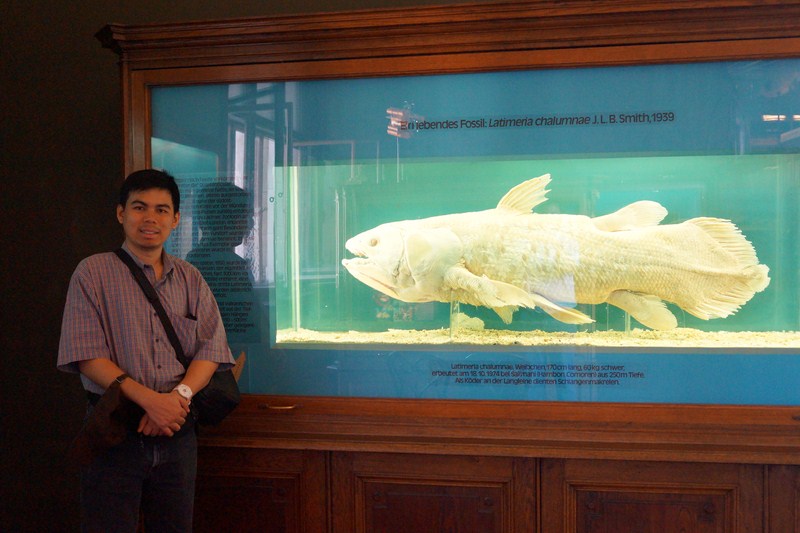

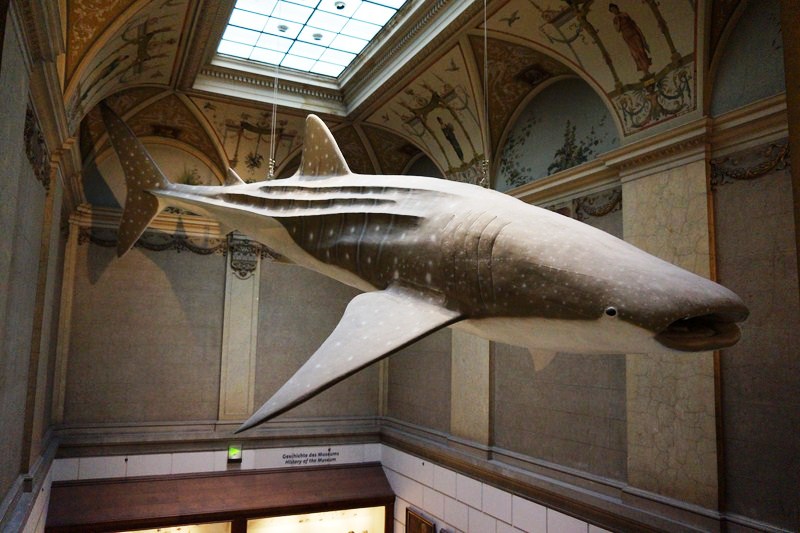

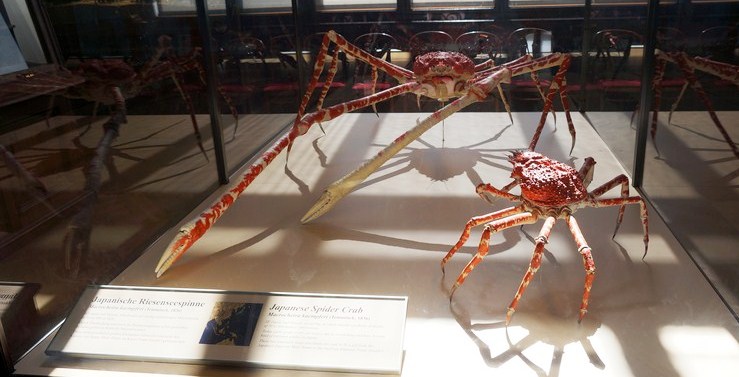

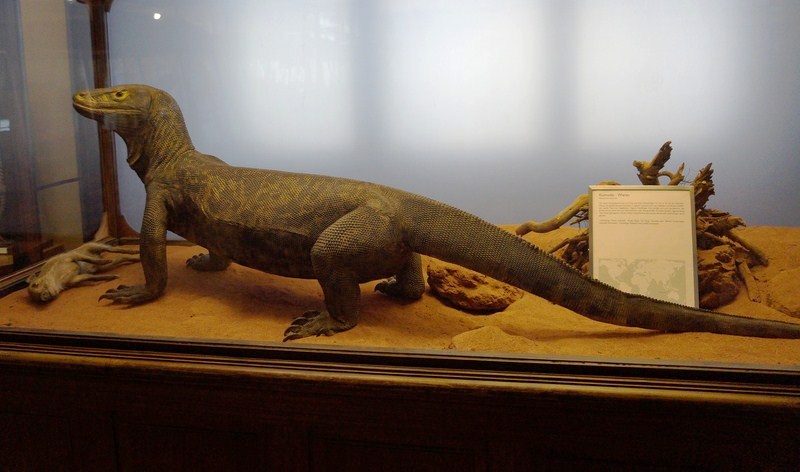

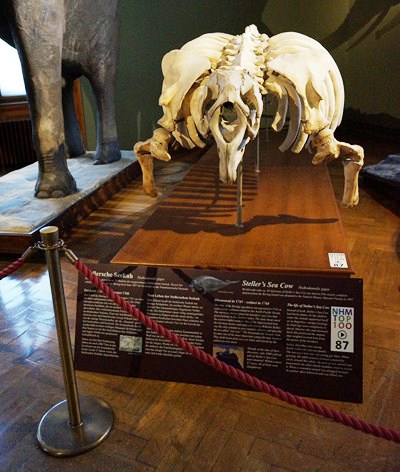

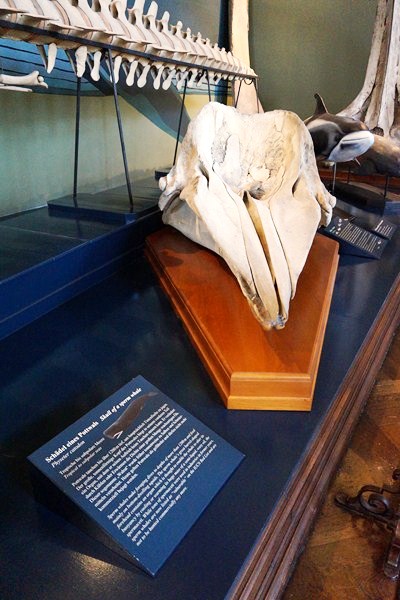

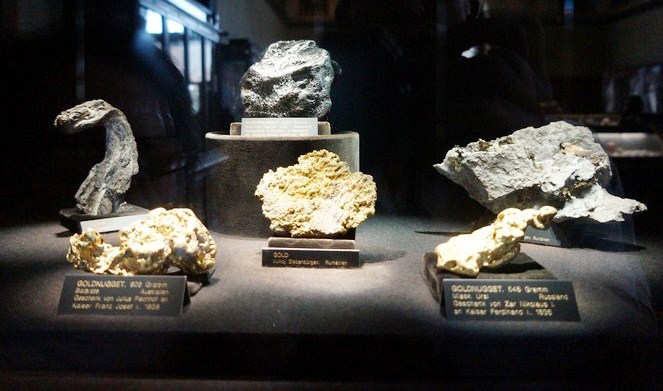

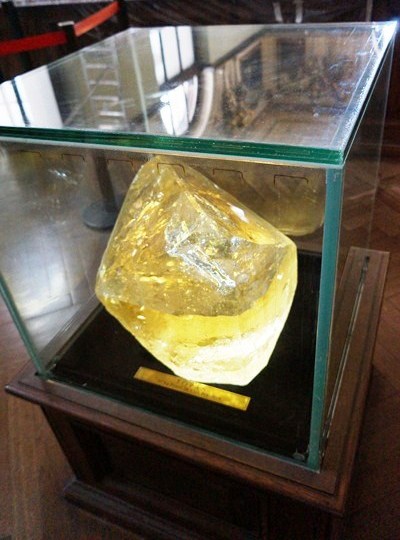

Of particularly interest are the desirable, exotic, rare, curious and unusual objects, often ascribed with magical powers, such as precious stones, ostrich eggs, coral and shark’s teeth, natural products from which artists created virtuoso works of art.

Among its highlights are numerous other art objects which have been collected since the Middle Ages such as carvings, timepieces, paintings, ivory sculptures, strange scientific instruments, wall-hangings, tapestries, coins, weapons, precious stone vessels, elaborate automatons, sumptuous game boards, drinking games and all sorts of humorous vessels, and a wide range of curiosities from the natural world.

They include examples of fabulous goldsmith work such as the celebrated and precious Saliera (“salt cellar,” which dates to the middle of the 16th century) by Benvenuto Cellini (at the heart of the collection) and the valuable gold and porcelain breakfast service of Maria Theresia; the so-called “Natternzungenkredenz” (around 1450), including fossil sharks’ teeth, considered to be the mystical remains of dragons; the natural cast of a real toad; outstanding sculptures such as the Krumau Madonna; magnificent bronze statuettes; a “Narwalhornbecher” from the 17th century claimed at the time to be made from a unicorn horn (actually a narwhal tusk); the Dragon Bowl made from lapis lazuli; delicate and bizarre ivories; carved rhinoceros horns, a valuable musical clock in the shape of a ship, a glass container (tafelaufsatz) shaped like a heron with real heron feathers; etc.

Each gallery, with its excellent design and layout carrying you along on a journey through changing times and techniques, has an overview explaining its theme and/or relevance to art and history. As you move from room to room, different art forms progressed, at different rates, in different regions.

Each item has an accompanying short description and touch screens provide further background information, more detail on selected exhibits and the genealogy of the Habsburg dynasty.

Gallery 19 (Golden Hall) impressed us with its huge ceiling painting “Mäcene the House of Habsburg,” the magnum opus of the now almost-forgotten history painter Julius Victor Berger which pays homage to the Habsburg art patrons and their favorite artists.

In Gallery 20 is the ivory collection of Emperor Leopold I, nephew of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm. They include the impressive ivory piece, from 1700, depicting Archduke Leopold adorned with angels, with a foot resting on his vanquished Ottoman foes following the famous defeats of the Ottoman armies, most notably at the Siege of Vienna in 1683 (though he was nowhere to be seen at that time in Vienna).

There’s also the detailed (check out the mind-blowing detail of the battle of Amazons) ivory and cedar reliefs, from the late 1600s and early 1700s, by Ignaz Elhafen; and the ivory reliefs by Johann Ignaz Bendl (he also contributed to the famous plague column in Vienna’s city center).

Gallery 22 displays the Master of the Furies, gorgeous ivory statuettes by an unknown artist, and a delightful ivory phoenix from 1610/1620.

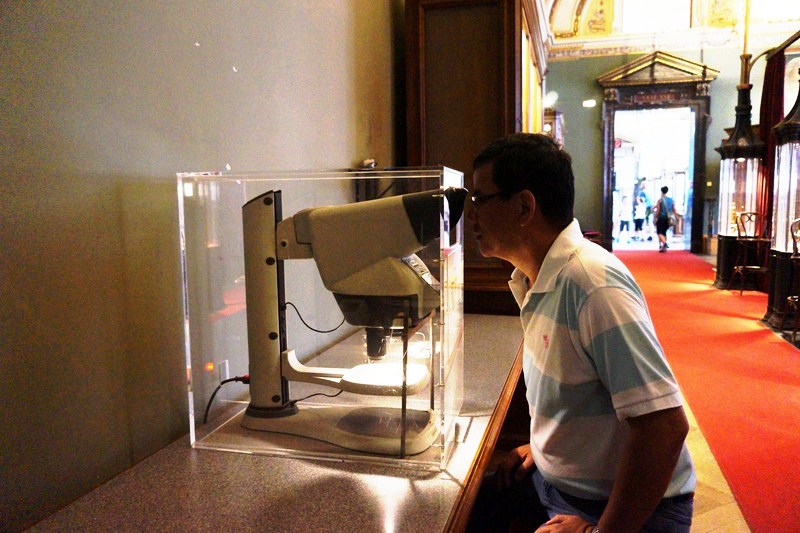

In Gallery 23 (to the side of Gallery 22), we found 17th century clocks and scientific instruments from the collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm.

Gallery 24, which continues the theme of intertwining nature and art, features items from the 16th century Innsbruck collection of Archduke Ferdinand II including the so-called hand stones (pieces of ore with biblical or mining scenes carved into them, with added decorative elements and models); plus pieces of glassware and crystal ware from Milanese workshops (e.g. Saracchi, Miseroni), many of which mimic the human body, plants, animals, and shells and often incorporate natural materials and surprisingly practical functions (a tortoise becomes a powder flask, a nautilus shell becomes a drinking vessel, etc.).

Dragon Shell (Gasparo Miseroni, 1565-70) features a fierce dragon motif in gold, enamel, rubies, emeralds and pearls

Gallery 25 houses some of the sumptuous and artistic settings of the Habsburgs such as rhino horns and ostrich eggs.

Often attributed with medicinal and magical powers by Europeans, these settings often served to emphasize the exotic nature of each of these items.

Displays include a figure of an African below an ostrich shell; a 1611 silver goblet made from rhino horn and decorated with warthog tusks; a giant 1592 basin and ewer decorated with pearl and garnets (its edges have metal casts of frogs and insects, in the 1500s people believed that putting one in a drink got rid of poison); and a large bezoar (indigestible masses found in the gastrointestinal system of animals, in this case a llama) on a gold, emerald and ruby base from the late 1500s.

Gallery 26, covering the stonecutting arts, features 17th century landscapes and cityscapes built, mosaic-like, from precious agate, jasper and hornstone. On display are a small private altar, from 1590/1600, which features Christ and the Woman of Samaria at Jacob’s Well by Gian Ambrogio Caroni, constructed from precious gems and metals (rock crystal, jasper, agates, lapis lazuli, emeralds, amethyst, gold, enamel, gilded silver and pearls).

Gallery 27, holding items from the Prague collection of Emperor Rudolf II, showed us how art, science and engineering began to combine with its displays of various automatons such as a mechanical ship from 1585 (the sails are miniature paintings); mechanical clocks from the late 1500s and early 1600s; sundials; vessels made of precious stone (believed to have healing or restorative powers), and much more.

There’s also a narwhal goblet, made of narwhal ivory, gold, enamel, diamonds, rubies, and agate, from 1600/1605; a gilded silver and enamel ornamental ewer and basin from 1601/1602; the bronze figure of a Flying Mercury, from 1585, by Giambologna; and the German Mercury figure.

Gallery 28 features measuring instruments; precious, 16th and 17th century carved coconuts gilded with silver; a wood, bronze and pearl cabinet from 1560/1570 designed for storing art.

At Gallery 29, we found the famous 1543 Saliera by Benvenuto Cellini (also known as the Cellini salt cellar), a golden salt and pepper dispenser for the table estimated to be worth about US$65 million. An allegory for the cosmos in gold, enamel, ebony and ivory, it was originally owned by King Francis I and given by King Charles IX of France, the king’s grandson, as a present to Archduke Ferdinand II.

Stolen in 2003 by an opportunistic passerby who scaled the scaffolding during renovations and disappeared off with the work, authorities recovered the Saliera in 2006 unharmed, found interred in a forest near Vienna.

In Gallery 30 is the Mompelgarder Altar, a ca. 1540, bright and colorful winged altarpiece created in the workshop of Heinrich Füllmaurer, whose many panels bear inscriptions from Martin Luther’s German translation of the Bible.

Gallery 31 features a sensational, incredibly detailed (check out the small flowers and distant backgrounds accompanying the two horsed emperors), carved backgammon set, from 1537. A statement of power and prestige, its pieces depict intricate literary scenes and its board back shows representations of the Habsburg dynasty, its lands, and its spiritual (though not actual) predecessors, such as Roman emperors.

At Gallery 32, we saw how art spread beyond its original (mostly religious) context, with artists starting to push back the borders of what’s possible. This is best illustrated by two bronze figures (ca. 1580), with its fluidity of apparent movement not seen in earlier bronzes, by Giambologna whose sculptures aim to create statues that invite you to walk around them. The gallery also displays an early automaton (or mechanical model) – a female musician from the late 1500s.

Gallery 34 displays 15th century figures and busts. Highlights here include the Vanitas Group of three figures, representing the beauty and transience of youth, carved from a single piece of limewood; a bronze statue of Bellerophon taming Pegasus, from around 1481 by Bertoldo di Giovanni, a pupil of Donatello (creator of the famous bronze David) and a teacher of Michelangelo (creator of another famous David); and a collection of plaquettes (small bronze reliefs) from the 15th century and later.

In Gallery 35 is the so-called Adder’s Tongues Credenza from around 1450, an ornament embedded with fossil shark’s teeth (considered to be dragon’s tongues, they were thought to sweat or change color when near poisoned food or drink) as well as a tiny, finely detailed boxwood rosary pendant displaying the Passion of Christ, a truly astonishing work of art.

Galleries 36 and 37 mainly feature ecclesiastical items from the 11th to 14th centuries which dominated early art. On display are a griffon-shaped aquamanile, basically a water jug used for the ritualistic washing of hands, from around 1125.

Kunskammer Wien: Raised Ground Floor, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Maria Theresien-Platz, 1010 Vienna. Tel: +43 1 525 24- 4902. E-mail: info.ansa@khm. Open Tuesdays – Sundays, 10 AM – 6 PM, Thursdays, 10 AM – 9 PM. Audio guides, in both English and German (see here for general visitor tips for the museum), are also available in the museum entrance hall..

How to Get There: take U1 going to Leopoldau at Keplerplatz, transfer to U2 going to Aspernstrabe at Karlsplatz, exit at Volkstheater.