Opened as a national museum (Museo Nazionale del Bargello) in 1865, its original structure, built alongside the Volognana Tower in 1256, had two storeys. After the fire of 1323, a third story, identified by the smaller blocks used to construct it, was added. During the 15th century, the palace was also subjected to a series of alterations and additions but still preserving its harmonious and pleasant severity.

Here are some interesting historical trivia regarding this building:

- Started in 1255, this austere crenelated building is the oldest public building in Florence.

- The word “bargello” appears to have been derived from the late Latin word bargillus (from Goth bargi and German burg), meaning “castle” or “fortified tower.” During the Italian Middle Ages, it was the name given to a military captain in charge of keeping peace and justice (hence “Captain of justice”) during riots and uproars. In Florence he was usually hired from a foreign city to prevent any appearance of favoritism on the part of the Captain. The position could be compared with that of a current Chief of police. The name Bargello was extended to the building which was the office of the captain.

- It is also known as the Palazzo del Bargello, Museo Nazionale del Bargello or Palazzo del Popolo (Palace of the People)

- This building served as model for the construction of the Palazzo Vecchio. Honolulu Hale‘s interior courtyard, staircase and open ceiling were also modeled after the Bargello.

- It was built to first house the Capitano del Popolo (“Captain of the People”) and, later, in 1261, the “podestà,” the highest magistrate of the Florence City Council (it was originally called the Palazzo del Podestà). In 1574, the Medici dispensed with the function of the podestà and housed the bargello, the police chief of Florence.

- Before it was turned into an art museum, it was a former barracks and prison during the whole 18th century. Executions, the most famous perhaps being that of Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli (involved in the Pazzi conspiracy against the Medici, which Leonardo da Vinci also witnessed), also took place in the Bargello’s yard until they were abolished by Grand Duke Peter Leopold in 1786, but it remained the headquarters of the Florentine police until 1859. When Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor, was exiled, the makeshift Governor of Tuscany decided that the Bargello should no longer be a jail, and it then became a national museum. It was also the meeting place of the Council of the Hundred in which Dante Alighieri took part.

- It displays the largest Italian collection, mainly from the grand ducal collections, of “minor” Gothic decorative arts and Renaissance sculptures (14–17th century).

Check out “Palazzo Vecchio“

The building is designed around a beautiful, irregular and unique open courtyard with an open well in the center. The walls of the courtyard are covered with dozens of coats-of-arms of the various podestà and giudici di ruota (judges).

The enormous entrance hall leading to the courtyard has heraldic decorations on the walls with the coats-of-arms of the podestà (13th-14th centuries). The courtyard has more coats-of-arms of the podestà. Under the porticoes are insignia of the quarters and districts of the city. Set against its walls are various 16th century statues by Baccio Bandinelli, Bartolomeo Ammannati, Domenico Pieratti, Niccolò di Pietro Lamberti, Giambologna and Vincenzo Danti.

The external open staircase leading to the second floor loggia, built in the 14th century, has various ornamental works by other 16th century artists including the delightful bronze animals made for the garden of the Medici Villa di Castello.

The first room to the right, formerly the Salone del Consiglio Generale but now the Donatello Room, contains many works of Donatello (1386-1466). The St. George Tabernacle (1416), moved to this location from the niche in Orsanmichele, is the very first example of the stiacciato technique, a very low bas-relief that provides the viewer with an illusion of depth, and one of the first examples of central-point perspective in sculpture.

Other works include the young St. John; the marble David (1408); the more mature and ambiguous bronze David (1430), the first delicate nude of the Renaissance; and the Marzocco, originally installed on the battlements of Palazzo Vecchio.

At the back wall of the Donatello Room are two bronze bas-relief panels, both competing designs for “The Sacrifice of Isaac” (Sacrificio di Isacco, the image had to include the father and son, as well as an altar, a donkey, a hill, two servants and a tree) made and entered by Lorenzo Ghiberti and Filippo Brunelleschi to win the contest for the second set of north doors of the Florence Baptistery (1401) in Piazza del Duomo. The judges chose Ghiberti for the commission.

Two rooms on the second floor are dedicated to the repertoire of glazed Renaissance terracotta sculptures created by Andrea Della Robbia, Luca Della Robbia (c. 1400 – 1482) and Giovanni Della Robbia. The glazed terracotta by Luca della Robbia includes a very extraordinary group of Madonna with Child.

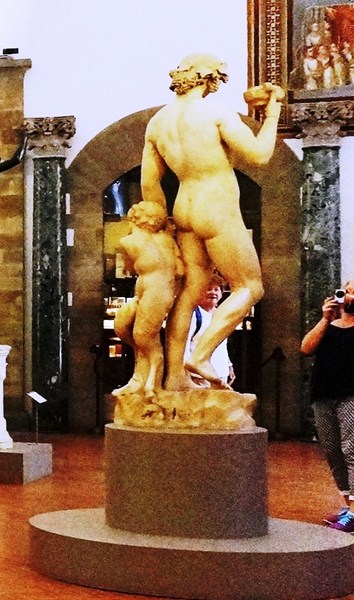

The large 14th century hall, on the first floor, displays a collection of 14th century sculpture, including works by Nicola Pisano. The rooms on the ground floor exhibit Tuscan 16th century works. The room closest to the staircase focuses, in particular, on four important masterpieces by Michelangelo (1475-1564): Bacchus (1470, the tipsy god of wine is being held up by a tree trunk and a little satyr), Pitti Tondo (relief representing a Madonna with Child), Brutus (1530) and David-Apollo.

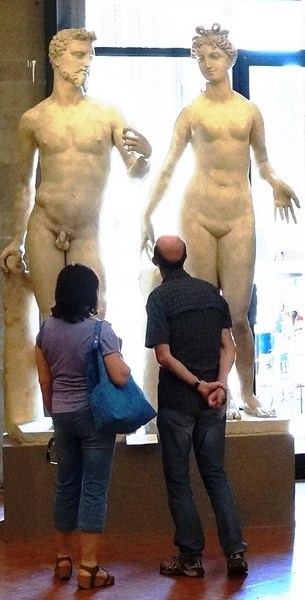

The assortment is then followed by works of Andrea Sansovino (1460-1529), Jacopo Sansovino‘s Bacchus (1486-1570, made on his own to compete against Michelangelo’s), Baccio Bandinelli (1488- 1560), Bartolomeo Ammannati (1511-1592), Benvenuto Cellini (represented with his bronze bust of Cosimo I and the model of Perseus and the small bronze sculptures, moved to this location from the Loggia dell’Orcagna), down to Giambologna (1529-1608) with his Architecture and the admirable Mercury; and Vincenzo Gemito‘s Il Pescatore (“fisherboy”).

There are a few works from the Baroque period, notably Gianlorenzo Bernini‘s 1636-7 Bust of Costanza Bonarelli. The staircases now display bronze animals that were originally placed in the grotto of the Medici villa of Castello. There are also sculptures by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo and others.

Also distributed among the several rooms of the palace, both on the first and second floor, are many other fine works of art enriched by the Carrand, Ressman and Franchetti collections comprising decorative or “minor” arts. They include ivories that include several Roman and Byzantine examples; Medieval glazes and Limoges porcelain from German and French gold works; Renaissance jewels; Islamic examples of damascened bronze; and Venetian glass; all from the Medici collections and those of private donors.

The bronze David and the Lady with Posy by Andrea del Verrocchio are in the room named after the artist.

Also on display are an extraordinary collection of busts of Florentine personalities made by some of the most important 15th century artists such as Desiderio da Settignano (c. 1430-1464) and Antonio Rossellino (c. 1427-1479), both pupils of Donnatello; Alessanro Algardi, Mino da Fiesole, Antonio Pollaiolo and others.

The museum also displays very unique panel pieces and wooden sculptures; ceramics (maiolica); waxes; goldwork and enamels from the Middle Ages to the 16th century; furniture; textiles; tapestries in the Sala della Torre; silver; arms and armor from the Middle Ages to the 17th century; small bronze statues, old coins and a very lavish collection of medals by Pisanello belonging to the Medici family.

Bargello Museum: Via del Proconsolo 4, Florence, Italy. Open Tuesdays to Fridays, 8.15 AM – 1.50 PM, closed on the 2nd and 4th Sunday and the 1st, 3rd and 5th Monday of each month. Admission: €4.00.

Pingback: My Homepage