The National Archaeological Museum of Florence (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze) was inaugurated in 1870 in the presence of King Victor Emmanuel II in the buildings of the Cenacolo di Fuligno on via Faenza. At that time it only comprised Etruscan and Roman remains. As the collections grew, a new site soon became necessary and, in 1880, the museum was transferred to its present location within the Palazzo della Crocetta, a palace built in 1620 for princess Maria Maddalena de’ Medici, daughter of Ferdinand I de Medici, by Giulio Parigi.

The collection’s first foundations were the family collections of the Medici and Lorraine, with several transfers from the Uffizi up to 1890 (except the collections of marble sculpture which the Uffizi already possessed).

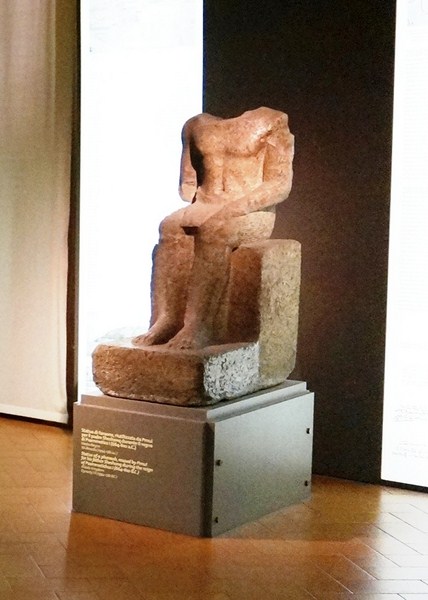

The Egyptian section, known as the Egyptian Museum, is the second largest collection of Egyptian artifacts in Italy, after that of the Museo Egizioin Turin. It was first formed in the first half of the 18th century from part of the collections of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany (Pierre Léopold de Toscane), from another part of an expedition promoted by the same Grand Duke and Charles X of France from 1828 to 1829 and directed by Jean-François Champollion (the man who first deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphic script) and Ippolito Rosellini (the father of Italian Egyptology, friend and student of Champollion who represented the Italian interests). During the expedition, many artifacts were collected, both from archeological diggings and via purchases from local merchants. On their return, these were evenly distributed between the Louvre in Paris and the new Egyptian Museum in Florence.

Officially opened in 1855, the museum’s first director was Ernesto Schiaparelli (who later went on to become director of the larger Egyptian museum in Turin) from Piedmont who, by 1880, had catalogued the collection and organized transportation of the antiquities to the museum. Under him, the collection expanded with further excavations and purchases carried out in Egypt. Many of the artifacts were, however, later transferred to Turin.

After this time, the Florentine collection continued to grow with donations from private individuals and scientific institutions. Expeditions to Egypt between 1934 and 1939, by the Papyrological Institute of Florence, provided one of the most substantial collections of Coptic art and documents in the world.

The museum, with a permanent staff including two professional Egyptologists, houses more than 14,000 substantially restored artifacts distributed in 9 galleries and two warehouses. A new, chronological and partly topographical system replaced the old classification system devised by Schiaparelli. The remarkable collection of stele, mummies, ushabti, amulets and bronze statuettes extends from the prehistorical era right through to the Coptic Age. There are statues from the reign of Amenhotep III; a chariot from the eighteenth dynasty; a pillar from the tomb of Seti I; parts of the burial equipment of Tjesraperet (a wet nurse of king Taharqo); a New Testament papyrus; and many other distinctive artifacts from many periods.

In 1887, a new topographic museum on the Etruscans was added but was destroyed during the 1966 floods. In 2006, the organisation of the Etruscan rooms was reconsidered and reordered and restoration was carried out on over 2,000 objects damaged during the 1966 floods.

Notable items on display include the Chimera of Arezzo (discovered in 1553 at Arezzo during the construction of a Medici fortress), the statue of the Arringatore (1st century BC), the funerary statue Mater Matuta (460–450 BC, returned to Chianciano Terme), the sarcophagus of Laerthia Seianti (2nd century BC) and the sarcophagus of the Amazons (4th century BC).

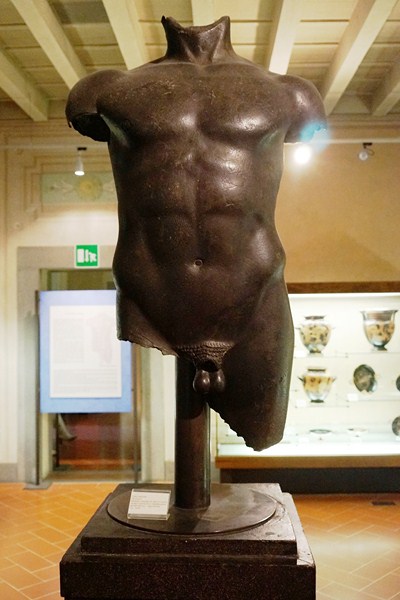

Notable objects in the Roman Collection include the “idolino of Pesaro” (a 146 cm. high bronze statue of a young man, a Roman copy from a classical Greek original, found in fragments in the centre of Pesaro in October 1530); the “torso di Livorno” (a copy of a 5th-century BC Greek original); the so-called “Gallo Treboniano” (a late 3rd-century statue of a cockerel); and the Minerva of Arezzo (a bronze Roman copy of a 4th-century BC Greek model attributed to Praxiteles).

The huge Greek Collection of ancient ceramics is located in a large room with numerous cases on the second floor. Generally the vases, evidence of cultural and mercantile exchange with Greece, and particularly Athens (where most of the vases were made), come from Etruscan tombs and date to the period between the 4th century BC and the present. The most important of the vases is the “François vase,” named after the archaeologist who found it in 1844 in an Etruscan tomb at fonte Rotella, along the Chiusi road. This large black figure krater (c. 570 BC), signed by the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias, shows a series of Greek mythological narratives on both sides.

Other notable objects on display include the red figure hydria signed by the Meidias painter (550–540 BC); the cups by the Little Masters (560–540 BC), named after their miniaturist style of their figures; the sculptures of Apollo and Apollino Milani (6th century BC, named after the man who gave them to the museum); the athlete’s torso (5th century BC); the large Hellenistic horse’s head (known as the Medici Riccardi head after the first place it was displayed, in the Medici’s Riccardi palace), fragment of an equestrian statue, which inspired Donatello and Verrocchio in two famous equestrian monuments in Padua and Venice; and two Archaic marble kouroi, displayed in a corridor.

National Archaeological Museum of Florence: Piazza Santissima Annunziata 9 B, Florence, Italy. Open Mondays, 2 PM – 7 PM; Tuesdays and Thursdays, 8:30 AM – 7 PM; Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturday, 8:30 AM – 2 PM; Holidays and Sundays, 8:30 AM – 2 PM. Admission: €4.00.