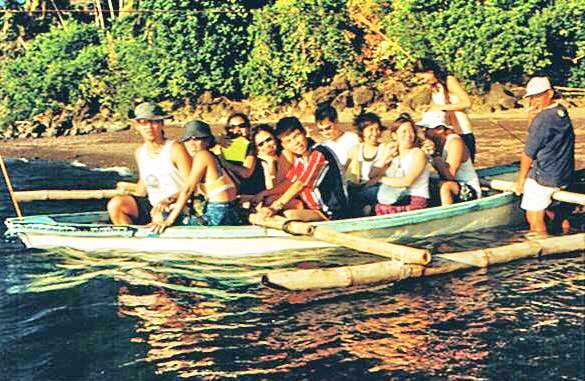

It being Good Friday, we fittingly made plans for a self-imposed, late afternoon Calvary-like hike, up Mt. Agalis, to the remote Pintong Alipi Falls. Bienvenido “Kit” Nazareno, Vener’s 55-year old uncle, volunteered to drive and accompany us there. The 30-min. jeepney trip to the jump-off point included passing by the 380-hectare, Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority (SBMA)-managed Bataan Technology Park in Brgy. Sabang. Now being developed as the “Silicon Valley of the Philippines,” this place used to have a humanitarian beginning, it being the former site of the Refugee Processing Center (PRPC), a refugee processing camp for Vietnamese “boat people.”

|

| A Vietnamese relic at Bataan Technology Park |

It was said that the PRPC was among the most comfortable refugee camps in the world. No barbwire fences and no border soldiers to accost the refugees coming in and out of the camp. Set up in 1979 under the United States Repatriation Program, it served as a temporary home and transit center for the relocation of Indo-Chinese refugees (Vietnamese, Khmers and Laotians) victimized by the American war in Southeast Asia. Here, they were trained in English, American history and vocational skills. The center housed 18,000 refugees at one time and more than 100,000 have passed through here.

|

| Remains of the first Vietnamese refugee boat |

Today, the PRPC is no more as it was closed in 1994. All we saw during transit was a shrine and the rotting remains of the first refugee boat to arrive there. Vietnamese cuisine, however, has left an imprint in the town. Near the town hall is a store serving hu-thieu, a soup concoction consisting of sotanghon noodles, sliced hard-boiled eggs, spices and bean sprouts. We sample this before we departed Morong for Manila. We, however, missed out on the bun-mi, another Vietnamese-inspired favorite which consists of grilled bun stuffed with pipino, tomatoes, onions and sliced meat with spices, mustard and mayonnaise added.

.jpg)