We departed Ben Thanh Market in our van during a driving rain and it was still raining when we arrived at the War Remnants Museum (Bảo tàng Chứng tích chiến tranh), perhaps the most famous and popular museum in the city.

The museum, opened to the public on September 4, 1975, attracts approximately half a million visitors every year, about two-thirds of them foreigners. Previously called the Museum of American War Crimes, the name was altered in 1995 so as not to cause offence to American visitors following the normalization of diplomatic relations with the United States and end of the US embargo the year before.

Comprising a series of themed rooms in several buildings (most in the former austere, concrete 3-storey United States Information Agency building), it primarily contains exhibits relating to the horrific American War (known in the U.S.A. as the Vietnam War), one of the bloodiest wars ever, also known as the second Indochina War, but also includes many exhibits relating to the first Indochina War involving the Vietnamese’ former French colonial masters.

The 8 main permanent exhibits and various other special collections are – “International Support for Vietnam in its Resistance” in the ground floor; “Agent Orange Aftermath in the U.S. Aggressive War in Vietnam” and “Aggression War Crimes” at the second floor; and “Historical Truths”, “Requiem,” the “War and Peace Pavilion” and “Agent Orange in the War” at the third floor. In another building is the “Imprisonment System” (shows the torture methods used in detention camps). Captions are in Vietnamese, English and Japanese.

This is also possibly one of the few museums in the world that allows you to take photos of the exhibits inside and outside. These exhibits took us a few hours to view and I concentrated more on the captions than a lot of the actual pictures. The copies of newspaper clippings are interesting.

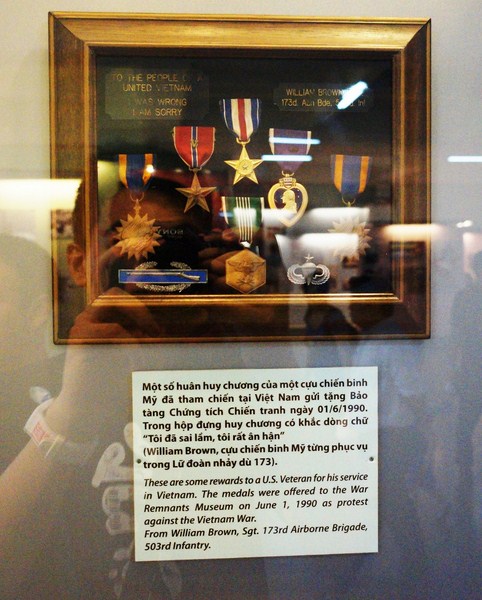

The “International Support for Vietnam in its Resistance Pavilion” is dedicated to the Vietnam peace movements all over the world, is devoted to a collection of posters and photographs showing international opposition (mostly communist countries such as Cuba, People’s Republic of China, the then Soviet Union, North Korea and prominent Western communist leaders) to the war as well as many old posters from the 1970’s American peace movement proclaiming “Stop the War.” A powerful exhibit here is the bunch of medals given by U.S. Sgt. William Brown to the Vietnamese people with an apology saying ‘To the people of an united Vietnam, I was wrong, I am sorry.”

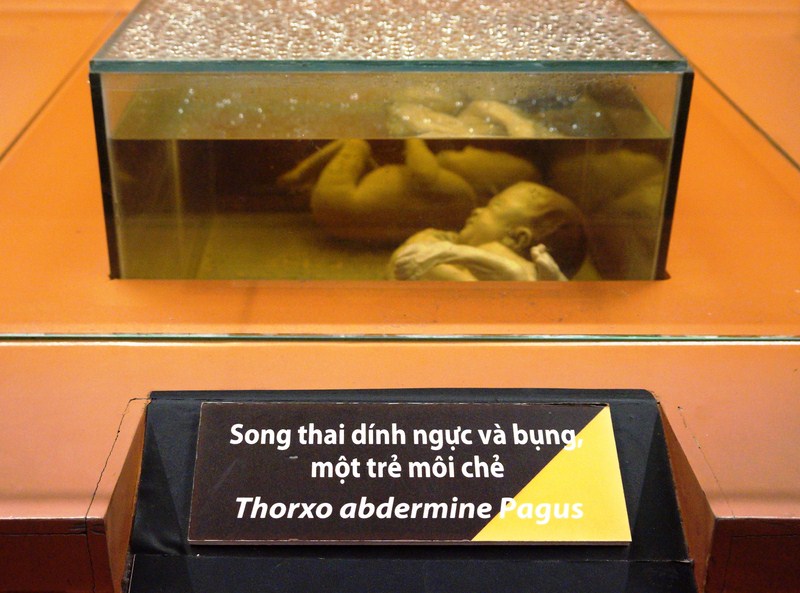

The “Agent Orange Aftermath in the U.S. Aggressive War in Vietnam Pavilion” covers the effects of Agent Orange and other chemical defoliant sprays. Prominent displays here include pictures of hideously deformed babies and three pickling jars of preserved human fetuses allegedly deformed by exposure to Agent Orange. They also have a video screening showing its effects on the Americans using chemical weapons during the war as well as highlight how the chemicals still affect the Vietnamese, even today.

The “Aggression War Crimes Pavilion,” a room at the second floor heavily dosed with anti-American propaganda, is a distressing compendium of the horrors of war that shows the mistreatment of civilians during the war through the use of napalm and phosphorus bombs and war atrocities such as the infamous My Lai massacre. Here, we had the rare chance to see some of the experimental weapons used in the war which were, at one time, military secrets, such as the fléchette, an artillery shell filled with thousands of tiny darts.

The “Historical Truths Pavilion,” devoted to the causes, origins and processes of aggressive wars, contains photographs, propaganda, news clippings, and signboards geared toward showing the wrongdoings of the U.S. government in the 1960s and 1970s.

The “War and Peace Pavilion” has a collection of colorful paintings submitted by schoolchildren from across Vietnam in response to a contest for pictures on the themes of war and peace and the healing of the wounds of war, is the most cheerful exhibit in the building. Some pictures are sad, others happy, but it does give you a sense of hope for the future. This somewhat upbeat and really uplifiting display provides some respite from the grizzly museum displays on the horrors of war. Children and adults alike can also draw on the free paper and pastels given out specifically to relieve stress.

The “Agent Orange in the War Pavilion” highlights America’s decision to use chemical weapons, giving emphasis to chemical weapon called “Agent Orange.” Dioxins and dioxin-like compounds were contained in 75 million liters of toxic chemicals which were dumped across the country including 44 million liters of the defoliant spray Agent Orange.

The excellent “Requiem Pavilion” houses a powerful and striking collection of assorted iconic photographs (some Pulitzer Prize-winning) and photo montages taken by 134 frontline journalists and photographers of 11 nationalities, on both sides, who were killed during the course of the conflict and compiled by legendary war photographer Tim Page.

This moving tribute includes works by Larry Burrows and Life Magazine’s Robert Capa who died on May 25,1954 stepping on a land mine. Pictures and short biographies of the photographers are by their featured photos.

This incredible collection of black and white photos (in some cases, very graphic that will distress viewers) from the American conflict is heart-wrenching and shows the deep suffering endured by the Vietnamese during the war. Most photographs are captioned with “His/her last photograph” or “The last sighting of them as they set off for a VC checkpoint.” The most moving, however, was “A chaplain reading their last rites.”

A photo that caught my attention was that of a mother fleeing away from her enemies with her children. Another one that struck me was the famous Pulitzer Prize winning photo of Huynh Cong Ut of a girl fleeing from the scene, being injured by the napalm bomb.

The rain had stopped and the sun was already shining when we finished our tour of the indoor exhibits, allowing us the opportunity to observe, up close, impressive state-of-the-art period military equipment placed within a now enlarged walled yard. The military equipment includes a UH-1 “Huey” helicopter, a BLU-82 “Daisy Cutter” bomb, M48 Patton tank, a renovated Douglas A-1 Skyraider attack bomber, an F-5A fighter and an A-37 Dragonfly attack bomber.

The last two are captured former South Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) aircraft. Stored in the corner of the yard are a ghoulish collection of unexploded ordnance , with their charges and/or fuses removed. When they called this place the War Remnants Museum, they weren’t joking.

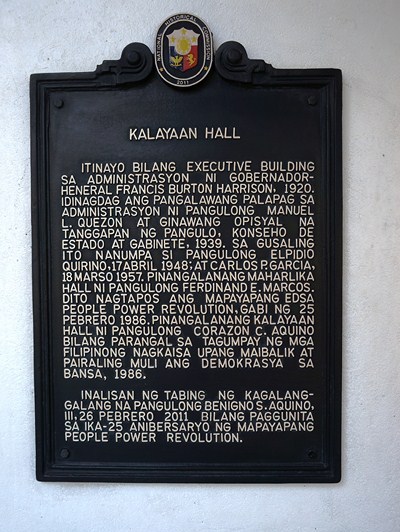

One corner of the grounds is devoted to the notorious French and South Vietnamese prisons on the infamous prison islands of Phu Quoc and Con Son near the Mekong Delta. Displays include the guillotine (that most iconic of French punishment devices) pictures, torture tools, and a grisly mock-up of the notoriously gruesome and inhumane “tiger cages” (with eerie wax models of prisoners sitting inside) used by the South Vietnamese government to house captured regular NVA prisoners-of-war, NLF (Vietcong) guerillas and political prisoners. The latter measures 2.7 m. x 1.5 m. x 3 m. and between 5 to14 prisoners were kept in each cage during the hot season, while only one or two were kept during the winter season.

The famous guillotine, brought to Vietnam by the French in 1911, was used in a jail along Ly Tu Trong Street. During the Vietnam War, it was transported to all of the provinces to decapitate Vietnamese patriots. Mr Hoang Le Kha, member of the Provincial Committee of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party in Tay Ninh province, was the last man executed in 1960.

A visit to the War Remnants Museum is a quite sobering experience, especially for people like me where war seemed so far away, making me value the peace that we have now. They make no attempt to sugar-coat what they have to say here – man’s inhumanity to man. This humbling and sorrowful tribute to the thousands of men, woman, and children that suffered death and injury was successful in driving home the fact that wars are brutal and that innocent civilians are the biggest losers. Their pains deserve to be remembered.

It’s certainly not a fun place to go to but an eye opener all the same. Much of what is on display isn’t easy to stomach, but that’s the point. Nevertheless, I would perhaps think twice about bringing children here. The prison cells can be especially scary for the little ones. Americans will probably say that it is extremely biased as its displays do tell the story from an anti-American perspective (not knowing that apparently 95% of the material came from the US archives) and it might be true. However, this powerful and politically charged testimony of the Vietnamese side constantly and subconsciously reminds us of the Winston Churchill’s idiom that “History is written by the victors.”

Disturbing, disgusting and tragic, the grisly photos of decapitated bodies and people begging for their lives, solemn, grim reminders of the cruelty of war, will open your eyes and churn your stomach. Still, I was still very glad that I went there. Their exhibits are compulsory viewing for all politicians worldwide. The museum gets busy in late afternoon as tours to the Cu Chi Tunnels (another good view of the Vietnam War),finish there. Avoid the crowds by going earlier in the day.

War Remnants Museum: 28 Võ Văn Tần, District 3, Hồ Chí Minh, Vietnam. Tel: (84-4) 39302112 and (84-8) 39306325. E-mail: warrmhcm@gmail.com. Website: www.warremnantsmuseum.com. Admission: 15,000 VND. Children below 12 years old are free and discounts are offered for some categories of people. Open Tuesdays to Sundays, 7.30 AM- 12 noon & 1:30-5 PM. Last admission is 4:30 PM.

How to Get There: if you are not within walking distance, there are different buses that go past the museum, . Bus Route No. 14: BX Eastern – 3/2 – BX West. Bus Route No. 28: Ben Thanh Market Cho Xuan Thoi Thuong Bus Route No. 06: Cholon BX – University of Agriculture and Forestry