The Renaissance-style, relatively little frequented Palazzo Medici, also called the Palazzo Medici Riccardi after the later family that acquired and expanded it, is the seat of the Metropolitan City of Florence and a museum. Located along Via Cavour (formerly Via Larga), close to the Church of San Lorenzo, the palace is the first Renaissance building erected in Florence and is a prototype of civil Renaissance architecture. Originally, the Palazzo Medici Riccardi was a cube shape with 10 windows across. Today, what we see is a rectangular building with 17 windows.

The palace, designed by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo (who was influenced in his design of the palace by both classical Roman and Brunelleschian principles) for Cosimo de’ Medici (head of the Medici banking family), was built between 1444 and 1484, after the defeat of the Milanese and when Cosimo de Medici had more governmental power.

The simple and modest exterior (though the inside was more decorated) of this building reflects the desire of the Medici family to keep a low profile, while exercising their power behind the scenes, after their return to Florence after their short exile in the early 15th century. This is said to be the reason why Cosimo de’ Medici rejected Filippo Brunelleschi‘s earlier too sumptuous and extravagant proposal (although Brunelleschi’s style can still be seen in the palazzo) for Michelozzo’s more modest design.

The palace remained the principal residence of the Medici family until Piero de Medici was exiled in 1494. Following their return to power, the palace continued to be used by lesser members of the Medici until 1540 when Cosimo I, after he became Grand Duke, moved his principal residence to the Palazzo Vecchio. Still, the younger family members continued to use the Palazzo Medici as a residence.

Check out “Palazzo Vecchio“

Its purposely plain exterior too austere for Baroque era tastes, the palace was then sold, in 1659, by Ferdinando II de Medici to marquise Gabriello Riccardi, his majordomo maggiore (probably the highest office in the Florentine court). Francesco Riccardi (a nephew of Gabriello who inherited uncle’s fortune when he died in 1675) had the palace renovated and commissioned Neapolitan artist Luca Giordano (a pupil of Pietro da Cortona) to do the magnificent gallery (probably one of the most beautiful and best-preserved Baroque halls in Italy).

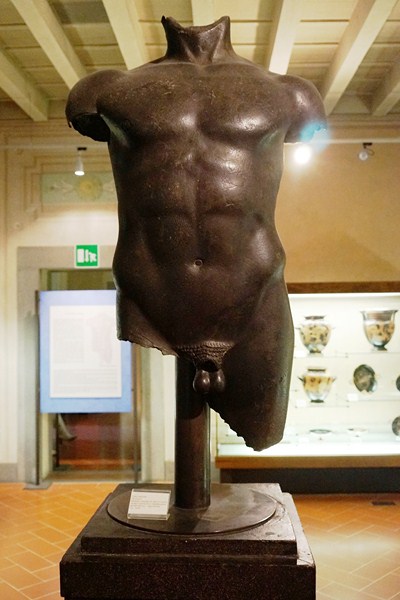

Frescoed with the Apotheosis of the Medici, Giordano, with the help of three collaborators, painted the entire gallery from mid-April to the end of August 1685. A new entrance staircase was also built by the architect Foggini and Baroque decorations were added also to the courtyard through the addition of old marbles belonging to the Riccardi collection.

In 1814, the Riccardi family sold the palace to the Tuscan state and, in 1874, the building became the seat of the provincial government of Florence.

Many significant events occurred in the palace:

- This palace was the main home of Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492), Cosimo the Elder’s grandson and the unmistakable Lord of Florence.

- In 1478, the Pazzi conspirators came to the palace to pick up Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano to accompany them to the nearby Duomo for mass with the intention of assassinating both (they only succeeded in killing Giuliano during the service).

- In 1489, a 14 year old Michelangelo came to live here as a teenage artist under the sponsorship of Lorenzo de Medici who actively sought to cultivate the development of young talent.

- In 1494, when the Medici were temporarily banished from the city, the citizens came to loot the building, taking away many of its Renaissance masterpieces.

- This palace was where Catherine the Medici, the future queen of France, lived as a little girl in the early 1500’s.

- The courtyard of the palace was where Donatello’s famous sculpture ‘Judith’ as well as his masterpiece, the bronze David, originally stood (both commissioned by the Medici).

- In 1512, soon after Giovanni became Pope Leo X, the first Medici pope, Lorenzo’s sons Giovanni and Giuliano return to this palace from exile to eventually rule Florence again – .

- In 1689, the palace was the site of the wedding reception between Ferdinando de’ Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany and Violante Beatrice of Bavaria.

- In 1938, a dinner between heads of state Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler was held in the Gallery Room of the palace.

The palace, well known for its stone masonry, uses building materials meant to accentuate the structure of the building through the threefold grading of masonry. By the use of rough texture to smoother textures as the building heightens, the rusticated blocks, on the ground floor, and ashlar for the face of the top story, create an optical recession that makes the building look even larger.

The huge cornice crowning the palazzo’s roofline (the first time it debuted fully developed) gave the palazzo more significance in a historical context. Through their choice of building material on the exterior, the Medici were still able to show their accumulated wealth and the costly and rare rusticated blocks soon became seen as a status symbol. A large part of power politics was believed to have started with the Palazzo Medici Riccardi.

The tripartite elevation, expressing the Renaissance spirit of rationality, order, and Classicism on a human scale, is emphasized by horizontal string courses that divide the building into stories of decreasing height. The building seems lighter and taller due to the transition, from the rusticated masonry of the ground floor, to the more delicately refined stonework of the third floor which makes as the eye moves upward to the massive cornice that caps, and clearly defines, the building’s outline.

Ancient Roman elements, both built and imagined in paintings during the Renaissance revival of Classical culture, were often replicated in architecture and, in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, the rusticated masonry and the cornice had precedents in Roman practice. However, in totality and unlike any known Roman building, it looks distinctly Florentine.

Michelozzo was influenced by the renowned sculptor and early Renaissance architect Brunelleschi who used Roman techniques. Two asymmetrical doors led to the typical fifteenth century open colonnaded courtyard (which originally opened on to a typically Renaissance garden) decorated with graffiti, a Brunelleschian design at the center of the palazzo plan, was based on the loggia of the Ospedale degli Innocenti and has roots in the cloisters that developed from Roman peristyles.

In 1517, the once open corner loggia and shop fronts, facing the street, were walled in and were replaced by Michelangelo‘s unusual ground-floor “kneeling windows” (finestre inginocchiate). These new windows, with exaggerated scrolling consoles appearing to support the sill and framed in a pedimented aedicule (a motif repeated in his new main doorway), are set into what appears to be a walled infill of the original arched opening, a Mannerist expression Michelangelo and others repeatedly used.

Different for its time, the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, believed to be the combination of Michelozzo’s traditional and progressive elements (that set the tone and style for future palazzo), was the start of several architectural breakthroughs:

- The palazzo was the first building in the city to be built after the modern order including its own separate rooms and apartments.

- The palazzo was also a start, to not only Michelozzo’s climb in status as an architect, but also as “the prototype of the Tuscan Renaissance palazzo” (which became a repeated style in many of his later work).

- It was one of the first buildings to have a grand staircase that was not a secular design.

- For a building of this time and the status symbol of the client at the time, it was a simple and modest-looking building.

- One of Michelozzo’s most important commissions for the family, it became a standard for other housing designed by him in years to come.

- The design of the palazzo, based on medieval design with other components added to it, was meant to be simpler but set, in such a way, that it still showed the wealth of the Medici family through use of materials, the interior and the simplicity.

The palazzo, divided into different, clear delineated floors, has a ground floor containing two courtyards, chambers, anti-chambers, studies, lavatories, kitchens, wells, secret and public staircases and, on each floor, other rooms meant for family.

The perfectly symmetrical Magi Chapel (Capella dei Magi), perhaps the most important section of the palace, had its entrance through the central door, which today is closed. Divided into two juxtaposed squares (a large hall and a raised rectangular apse with an altar and two small lateral sacristies), it was begun around 1449-50. Its precious ceiling of inlaid wood, painted and generously gilded according to Michelozzo’s design, is attributed to Pagno di Lapo Portigiano.

The flooring, of marble mosaic work, is divided by elaborate geometric design which, due to the extraordinary value of the materials (porphyries, granites, etc.), affirmed the Medicis’ desire to emulate the magnificence of the Roman basilicas and the Florentine Baptistry. A wooden baldachin, its architectural design attributed to Giuliano da Sangallo, around 1469, is worked in inlay and carving.

The first pictorial element in the chapel is the altar panel bearing a copy, attributed to the Pseudo Pier Francesco Fiorentino (a follower of Filippo Lippi), Filippo Lippi‘s Adoration in the Forest which was sold during the last century and today is in Berlin. In 1992, the original beauty of the painting was restored.

The famous frescos, by Benozzo Gozzoli who completed it around 1459, were adorned with a wealth of anecdotal detail and portraits of members of the Medici family including family members (Cosimo, his son Piero, and grandson Lorenzo the Magnificent) and their allies, along with wealthy protagonists Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos and Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg parading through Tuscany in the guise of the Three Wise Men.

Many of the depictions, regardless of its biblical allusions, explicitly referred to the train of the Concilium that met in Florence during the Council of Florence (1438-1439), an event that brought prestige to both Florence and the Medici.

The Angels in Adoration are in the rectangular apse and the Journey of the Magi are in the large hall. The sumptuous and varied costumes, with their princely finishing, make this pictorial series one of the most fascinating testimonies of art and costume of all time. The frescoes were restored from 1987 to 1992.

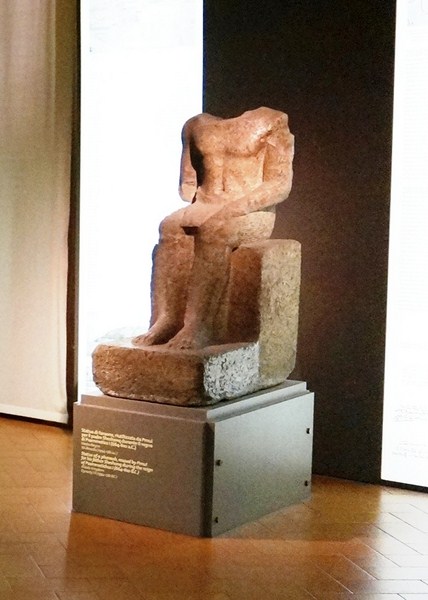

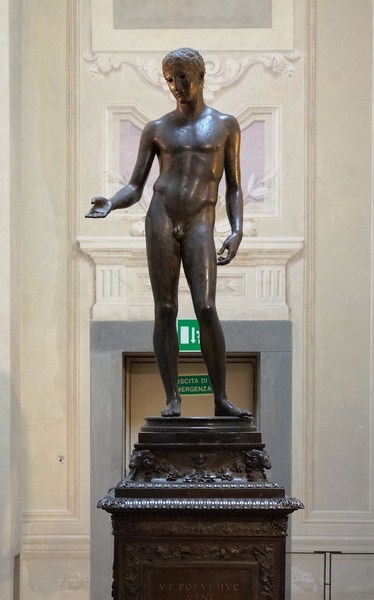

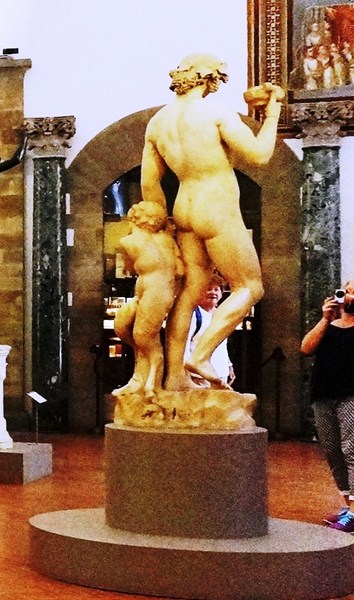

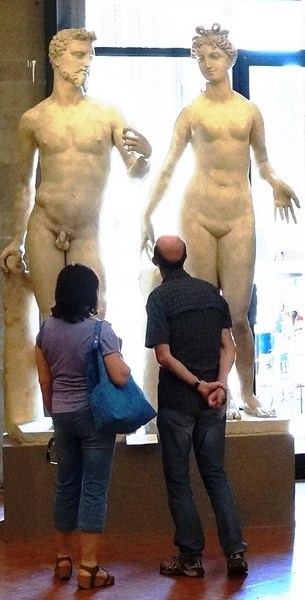

The Palazzo also displays works by Donatello, namely the statues David, displayed in the courtyard, and Judith and Holofernes, displayed in the garden. Two lunettes, by Filippo Lippi, depicting Seven Saints and the Annunciation, are both now at the National Gallery, London.

The courtyard of columns has huge stone friezes decorating the walls. Above it is a portico decorated with cameo-style carvings.The palace also has an interactive media room (in what was once Lorenzo’s bedroom) and conference rooms (still in use today) decorated with 17th-century tapestries.

Palazzo Medici Riccardi: Via Camillo Cavour 3, Florence, Italy. Open daily (except Wednesday), 9 AM to 7 PM. Tel: (+33) 0 55-276-0340. Website: www.palazzo-medici.it. Admission: €7.00 (adults), €4.00 (children aged 6 to 12, military categories) and free for the disabled and their caretakers. Ticket sales close at 6.30 PM.

Entrance to the Chapel is limited to a maximum of 8 visitors every 7 minutes Bookings operate on a “fast lane” basis, offering priority entrance at the beginning of every hour(from 9 AM to 6 PM) for a maximum number of 25 people at a time. Visitors who have booked should report to the ticket office at least 15 minutes before the booked time.

How to Get There: C1, 23, 14 stop Pucci