Shota Rustaveli Avenue, the central avenue in Tbilisi formerly known as Golovin Street, was built in the 19th century when M. S. Vorontsov was ruler of Georgia, was divided into two parts – Palace Street and the Golovin Avenue. In 1918, it named after medieval Georgian poet Shota Rustaveli, author of the immortal poem “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.”

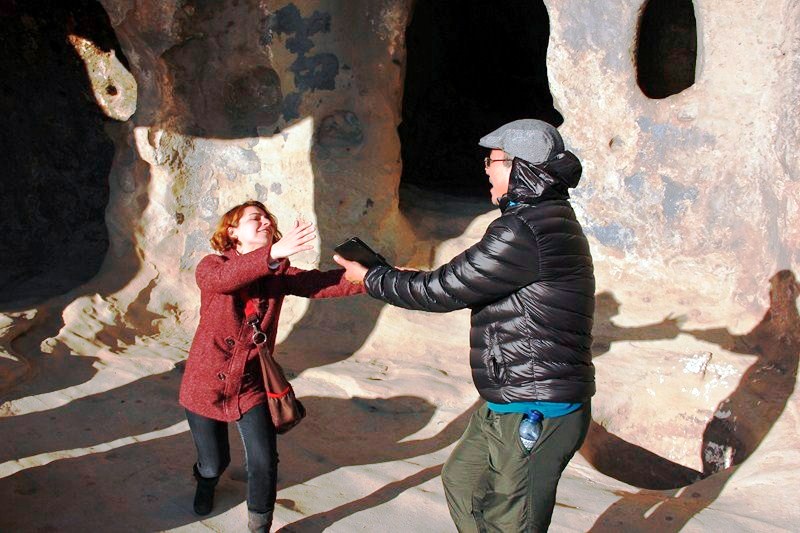

The author (in blue jacket) walking among a sea of Georgians, all in dark-colored jackets and overcoats (photo: Ms. Riva Galveztan)

A popular place for walking, I strolled along Rustaveli to soak up the bustling, cosmopolitan atmosphere of Tbilisi’s main thoroughfare which is lined with Oriental plane trees (Platanus orientalis) and strung with a handsome mix of modern and 20th-century architecture, with a contrasting European/Russian (Neo-Classical) look, such as important governmental, public, cultural, and business buildings as well as various cafes, shops, restaurants and other entertainment places.

This fine, stately avenue, which leads off to the northwest, is one of the best architectural and tourist centers of Tbilisi. However, it is spoilt by the amount of traffic roaring up and down it these days. There are a number of pedestrian underpasses, but people here also cross the road with great nonchalance, waiting on the centre line until there’s a gap.

Rustaveli Avenue (Rustavelis Gamziri in Georgian or Rustaveli Prospekt in Russian) starts at Freedom Square and extends for about 1.5 kms. before it turns into an extension of Kostavas Kucha (Kostava Street). Also branching out from this square are five other streets – Pushkin Street, Leselidze Street, Shalva Dadiani Street, Galaktion Street, and Leonidze Street. At its far end is the Freedom Square Metro Station at Rustaveli 6 where I alighted and started my stroll.

Freedom Square, first called Yerevan Square was, later in the Soviet period, renamed after Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria and then after Vladimir Lenin. In the center of Freedom Square (once occupied by a monument to Lenin which was symbolically torn down in August 1991) is the Monument of Freedom and Victory, a fountain with a very tall 40 m. high column topped by a bronze statue of St. George slaying the Dragon, a gift, unveiled on November 23, 2006, of famous Georgian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli to his native city.

The entire southern line of the square is occupied by the main Pseudo Moorish-style facade of Tbilisi Sakrebulo (City Assembly), a former town council building built in 1880 by German architect Peter Stern. Its third storey, with a clock tower, was built between 1910 and 1912. This attractive building, with stripes of sandy green and white and mauresque stucco, now houses, at the eastern side of the ground floor, a well- equipped tourist information office, with plenty of free booklets, maps and helpful English-speaking staff, plus outlets of Burberry, Chronograph and Chopard.

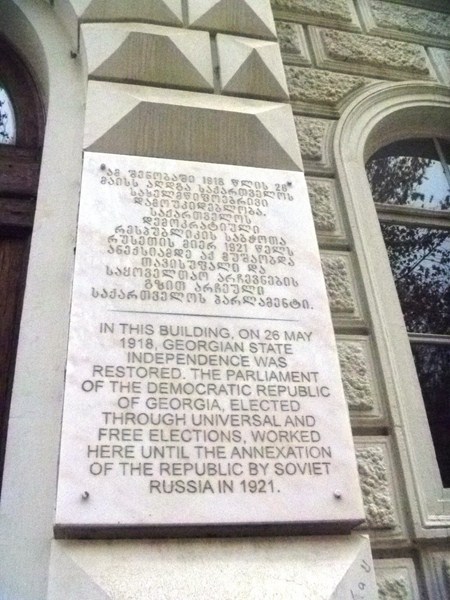

The Tbilisi National Youth Palace, erected n 1802, was rebuilt many times, the last time from 1865-1868 when the building was enlarged by architect O. Simenson who added an arcade in front. From 1844 to 1917, the building was the residence of the Russian vice-regent in the Caucasus. On May 26, 1918, during the meeting of the Transcaucasian Seim, the Georgian delegation left the hall and, in the adjacent White Hall, proclaimed Georgia a sovereign country.

At one time, Josef Stalin installed his mother here. On May 2, 1941, during the Soviet period, it served as the Pioneers’ Palace, housing the Soviet youth organization and a Museum of Children’s Toys. Still used for youth activities, it is the best place to find classes and displays of Georgian folk dance and the like. Around the palace is a well-kept garden, the back part of which faces Ingorokva Street. Aleksey Yermolov, the former Caucasian commander-in-chief, paid special attention to this garden, planting two large plane trees. In the past, the garden belonged to a princess of the Orbeliani family.

Beyond the National Youth Palace is the Parliament Building, easily the most dominating building along Rustaveli Avenue. Designed by architects Victor Kokorin and Giorgi Lezhava, it was built as a U-shaped block in 1938 (on the site of the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, built in the 19th century for the Russian army), it’s very solid portico of tuff was built by German prisoners-of- war and the building was opened in 1953. Its 16 columns symbolize the 16 Soviet republics.

The National Picture Gallery (Blue Gallery), built in 1885, was erected by the German architect Zalzman as the “Temple of Glory” to commemorate the victory of the Russian troops over the Persians. The trophy cannons recaptured from the Persian army, stood in front of the building in the last century.

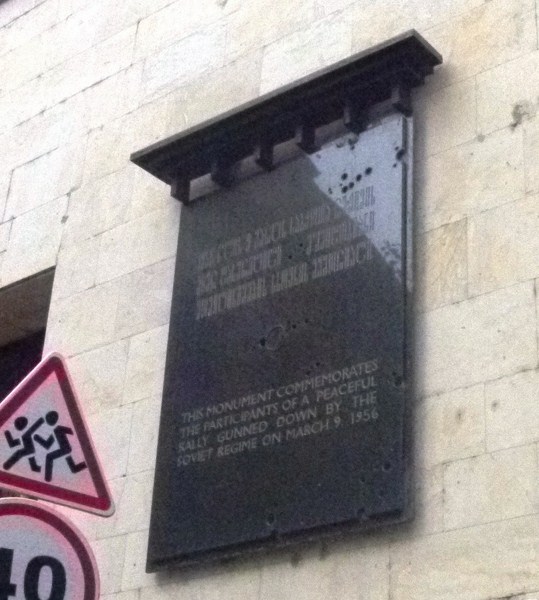

Immediately beyond the Parliament Building is the High School No. 1, founded in 1802 as the first European-style high school in Transcaucasia. It educated many of the leading figures of recent Georgian history, including Merab Kostava, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Tengiz Sigua and Tengiz Kitovani.

A good example of Russian Neo-Classicism, it has statues of Ilia Chavchavadze and Akaki Tsereteli (1958) in front. It houses the Museum of Education. A plaque here commemorates those killed by the Soviet security forces on March 9, 1956.

Past the school, Rustaveli Avenue bends to the left and I found myself in front of the Tbilisi Marriott Hotel (No. 13), one of the massive constructions of the 20th century. Elegantly emphasizing the avenue’s bend, this building, opposite the Ministry of Transport and Communications, was designed by ethnic Armenian architect Gavriil Ter-Mikelov in 1915 as the Hotel Majestic.

Later, it was renamed as Hotel Tbilisi. During the 1991-1992 Civil War, the hotel was burned and was later restored and reopened in 2002 as the luxurious Marriott Hotel.

Next to the hotel is the famous, splendid Rustaveli State Academic Theater (No. 17), one of the most beautiful buildings along the avenue. Designed by architects K. Tatishev and Alexandre Shimkevich in the French Neo-Classical style from 1899 to 1901, in the past it housed the Actors’ Society Club.

Its ornate architecture involves the forms and motives of the Late Baroque Period, with mirror windows and a large portal. The theater was refurbished from 1920 to 1921, for the new Rustaveli Theatre Company, and was refurbished again from 2002 to 2005. Since 1921, the theater has carried the name of Shota Rustaveli, Georgia’s national poet. In 2006, a Hollywood-style “Walk of the Stars” was begun in front.

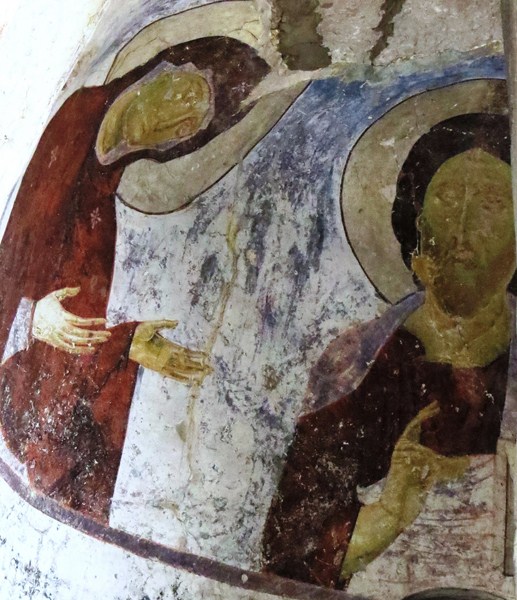

It now houses a first-class theater, a large concert hall, a large and small ballroom, a small foyer, marble staircases, classical statues and a number of big and small rooms for the Actors’ Society Club. It has three stages – a main stage (about 800 seats), a smaller stage (300 seats) and a Black Box Theater (182 seats) for experimental performances. The Kimerioni (Chimera) Cafe-Bar, at the lower floor of the theater, has frescoes painted in 1919 by prominent Georgian painters Lado Gudiashvili and David Kakabadze, theater set designer Serge Sudeikin as well as Sigizmund Valishevski (he was called Ziga in Tbilisi) and Moise and Iracly Toidze. Nearby is the Theatrical Institute.

Not far from the Rustaveli State Academic Theater, along the north side of Rustaveli, is the elegant Paliashvili Opera and Ballet Theater (No. 25). Formerly the Public Theater, it was first built in 1851 but burned down on October 11, 1874. The present Moorish-Eastern style building was designed by architect Viktor Schroter and built from 1880 to 1896.

In 1937, the theater was renamed in honor of Zakaria Paliashvili, one of Georgia’s greatest composers. It too burned down in 1973 but was rebuilt in 1977. Its towers, arches, turrets, stained glass windows, ornaments and intricate molding at the front entrance were all laboriously and meticulously made with special care.

The theater hosted, at different times, opera singers such as Fedor Shaliapin (who said “I was born twice: for life – in Kazan, for music – in Tbilisi”), Sergei Lemeshev, Vano Sarajishvili, Zurab Sotkilava, Paata Burchuladze, Jose Carreras and Montserrat Caballe; and ballet dancer Vakhtang Chabukiani.

Nearing the end of Rustaveli Avenue, I espied another monumental building – the former Georgian branch of Marxism-Leninism Institute. Designed by architect A. Shukin and built in 1938, its frieze is decorated with bas reliefs made by Iakob Nikoladze. Since 1993, the Constitutional Court has had its sittings there. Today, it is now home to a 200-room hotel, 50 apartments and 8 penthouses designed by Alexey Shuyev and managed by Kempinski Hotels. The new building, incorporating the historic main façade, features a domed hotel lobby and an octagonal courtyard.

Just at the end of Rustaveli is the Georgian National Academy of Sciences, a pompous building designed by architects K. Chkheidze and M. Chkhikvadze in 1953. It has a beautiful, low Italian-style colonnade; a solemn, angular tower revetted with Bolnisi tuff.

Between its columns is a through arcade where you can go to the lower station (which has an oval design) of the cableway leading to the upper plateau of Mtatsminda. On the steps of the academy artists and craftsmen sell their works.

My walking tour of Rustaveli Avenue was completed upon reaching the monument to the poet Shota Rustaveli, made by a sculptor K. Merabishvili.