The Church of St. Peter Martyr (Italian: Chiesa di San Pietro Martire), currently one of the two main Roman catholic parish churches (the other is the Basilica of St. Donato) and one of three remaining (before Napoleon there were 18, the third is the Church of St. Mary of the Angels ) in the island of Murano, near Venice, was edificated in 1348 along with a Dominican convent and was originally dedicated to St. John the Baptist. In 1474, a fire razed it to the ground and, in 1511, it was rebuilt and enlarged to the current appearance and rededicated to St. Peter Martyr.

In 1806, a few years after the fall of the Republic of Venice, it was closed but was reopened in 1813 as a parish church due to an initiative by Fr. Stefano Tosi, with art from other suppressed churches and monasteries on Murano and other islands. At its reopening the church was renamed St. Peter and Paul (S. Pietro e Paolo) but, in 1840, it reverted to its present name.

During the restoration of 1922-28, the original ceiling and the frescos of the saints above the pillars were revealed. The colonnade from the demolished convent of Santa Chiara was also reassembled and attached to the west flank of the church in 1924. From 1981 to 1983, the church underwent a restoration campaign financed by the Italian Ministry of Culture. The roof was repaired and the rotten brickwork was replaced. Save Venice provided emergency funding to repair stone parts of the two-light “bifora” window above the side entrance door.

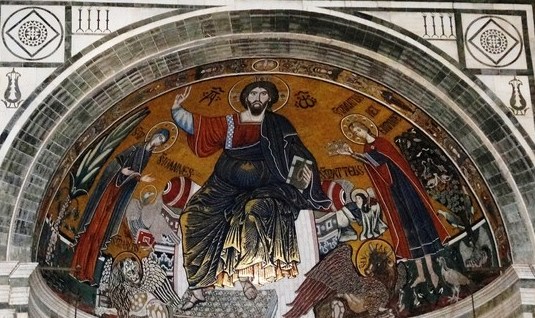

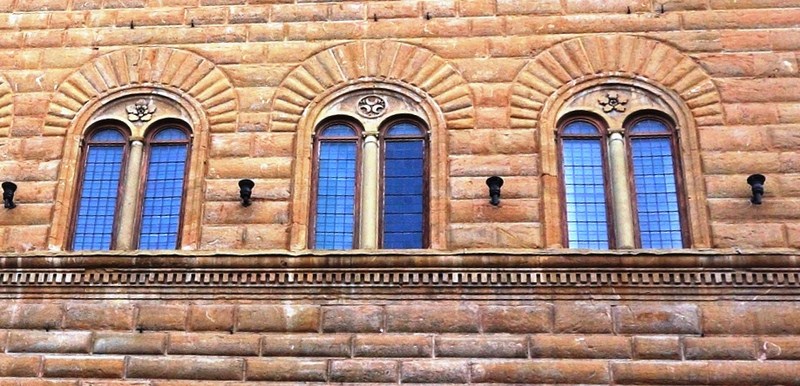

The church’s Renaissance façade, of naked brickwork, is divided in three sections. Its 16th-century portal is surmounted by a large rose window. On the left façade is a portico with Renaissance arcades and columns (perhaps what remains of the original cloister) and a bell tower, dating to 1498-1502 (its original bells came from England but have been recast many times since, most recently in 1942 after war damage). The church is 55 m. (180 ft.) long, 25 m. (82 ft.) wide and 13 m. (43 ft.) wide at the nave.

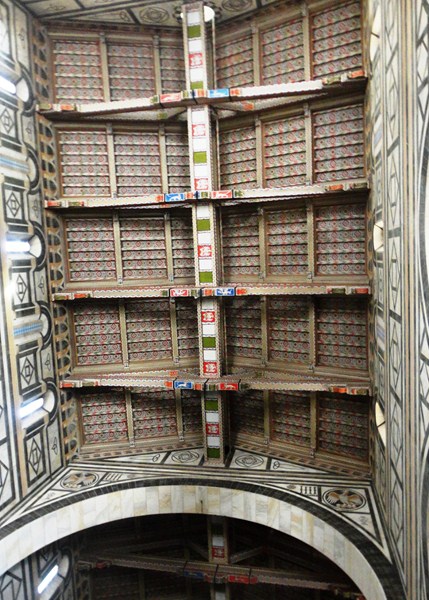

The impressively spacious and tall interior, with a basilica plan, has a nave and two aisles (divided from each other by rows of four arches supported by large columns), a wooden ceiling, tie beams across the arches and the nave, a trussed roof, a wide and deep half-domed chancel, a high altar and three minor altars for each nave. The spandrels between the arches are nicely decorated with saints. The quite large presbytery has barrel vaults and two small, wide and deep apsidal chapels.

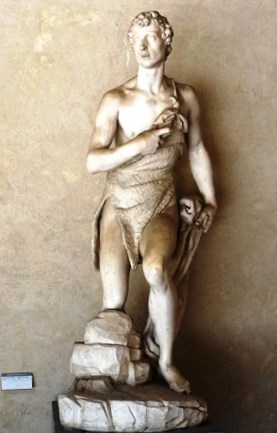

In the right nave are artworks including a Baptism of Christ (attributed to Tintoretto, it came from above the high altar of the demolished San Giovanni dei Battuti on Murano) plus two works by Giovanni Bellini – Assumption with Saints (1510–1513) and the Barbarigo Altarpiece (or The Madonna with Doge Agostino Barbarigo, 1488), taken from the nearby church of Santa Maria degli Angeli and brought here in 1815.

Other paintings include a St. Jerome in the Desert by Paolo Veronese (also from Santa Maria degli Angeli), St Agatha Visited in Prison by St. Peter and an Angel (also by Veronese), the Barcaioli Altarpiece (or Virgin and Child with Saints) by Giovanni Agostino da Lodi (ca. 1500, it was previously thought to be by Basaiti and came from the demolished San Cristoforo delle Pace), a Deposition from the Cross by Giuseppe Porta, Saints Nicholas, Charles Borromeo and Lucy by Palma il Giovane (which came from the demolished church of Santi Biagio e Cataldo on Giudecca) and a 1495 Ecce Homo (perhaps from the destroyed church of Santo Stefano in Murano). In the left-hand apsidal chapel is a hard-to-see painting by Domenico Tintoretto while a pair of huge paintings by Bartolomeo Latteri (including an impressively architectural Nozze di Cana) covering both side walls of the deep chancel.

The Ballarin Chapel, at the church’s right wing, was built in 1506 after the death of Giuliano Ballarin, the eponymous glassmaker from Murano.

Chiesa di San Pietro Martire: Fondamenta dei Vetrai, Campiello Marco Michieli 3, 30141 Murano, Venice VE, Italy. Tel: +39 041 739704. Open Mondays to Saturdays, 9 AM – 12 noon and 3 – 6 PM, and Sundays, 3- 6 PM.