|

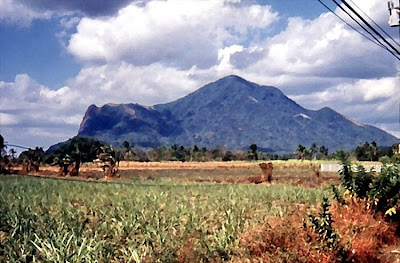

| Mt. Makulot |

Jandy and I checked out of Casa Punzalan in Taal early in the morning and proceed to Cuenca, passing by the towns of Sta. Teresita and Alitagtag. We planned to climb the 1,145 m. high Mt. Makulot, the highest mountain in Batangas. The weather was perfect. Mt. Makulot (also called Macolod), located at the northeast boundary with Laguna, is said to have been named after the kinky-haired people who lived on the mountain. The mountain dominates the southeastern shore of Taal Lake and has a rounded, densely-forested main summit and an extended shoulder on the west flank which ends abruptly in a 700-m. rocky drop-off. The mountain is thought to be the highest part of the caldera rim that was not blown away in Taal’s ancient eruptions. Others say the mountain is part of another extinct volcano. It was the last Japanese stronghold in the province during World War II, and 5 Japanese-built tunnels still exist in the area. To preserve the mountain for future generations, the mountain was adopted by the Philippine Air Force, under then commanding Gen. William Hotchkiss, on February 21, 1998.

|

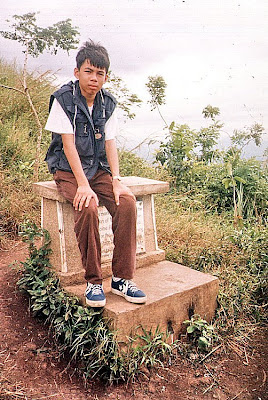

| The Philippine Air Force Marker |

Upon entering Cuenca town, we stopped at the town hall where we were advised, as a safety measure, to register (PhP5 per person) at the Barangay 7 hall. After registration, we were given a quick lecture lecture on how to get to the campsite. I parked our Nissan Sentra at the Mountaineer’s Stop-over Store. At the last minute, I decided not to bring my camping equipment and to just go on a day hike up to the mountain’s shoulder. I wanted to go home early. We donned jackets, changed into rubber shoes and packed 5 bottles of mineral water, my camera, extra shirts, my cell phone and a first aid kit.

|

| The Rockies |

The initial trail is a fairly gentle, moderate grade section through a gravel path. After passing some residential houses, including an expensive-looking one, and entering a forest, we reached a fork along the trail. Remembering the lecture, we took the left trail (the one descending), and went past a dried rivulet and another fork. We asked around and were told to take the right trail. We were also told that the left trail leads to a staircase down a cliff to the lake shore. Surely for the more adventurous. The trail became steeper (and more lung-busting) as we entered the forest. We needed both hands to hold on to roots and branches of trees. Rest stops became more frequent. All the while, hikers, as well as local residents, were passing me by. I was shamed by the sight of a woman carrying a heavy load of long bamboo stems. As we went along, I befriended a man laden with two backpacks and an icebox full of soft drinks, all slung on a pick. Named Eduardo Puso, he was a Barangay 7 tanod on his way to bring supplies for his store on top of the mountain. His two sons, Eduardo Jr. and Ramon, also carrying provisions, passed me by a while earlier.

|

| The knife’s edge leading to the Rockies |

The last quarter of the hike was through an even narrower path through tall cogon grass which swayed in rhythmic, wave-like motions when the wind blew. At around 11:30 AM, we reached the campsite at the mountain’s shoulder. Mang Ed and his sons were already tending to their store, which is beside another store tended by a woman. Even on this mountain, the spirit of healthy competition lives on. The campsite, Makulot’s main attraction, is actually a small clearing on the cogon-covered shoulder. We explored a small trail through the cogon grass leading to a clearing with a marker installed by the PAF.

|

| The fog-covered peak |

Here, we were presented with an impressive view, the best I’ve seen so far, of Taal Lake, Lipa Point, Volcano Island, the surrounding towns and beyond it, Laguna de Bay and the sea. Over a knife’s edge is the 700-m. drop-off (500 m. of which are almost vertical). Locals call it the “Rockies” after its American namesake. We returned to Mang Ed’s store and I interviewed him about the mountain. He said that Makulot has 14 Stations of the Cross frequented by townsfolk during Holy Week. Trekkers and campers come here even in adverse weather conditions and peak days are Fridays to Sundays when up to 200 campers converge.

|

| View of Volcano Island |

Mang Ed opens his store only during those peak days. Set up with money borrowed from a “five-six” loan shark, the store offers cigarettes, bread, candies, soft drinks in cans, real buko juice and, only on request, cooked food. When provisions run low, he quickly sends his sons down the mountain for supplies. Prices are high, but understandably so considering the labor involved. Mang Ed, being an elected barangay tanod, sees to it that the campsite remains clean. He frowns on campers who leave their rubbish behind. Just the same, he and his sons gather the trash and carefully burn it. They also assist in bringing down badly injured campers on a stretcher and advises climbers not to go beyond the Rockies. In 1994, a woman fell to her death (some say it was a suicide). In 1997, another man fell but survived. He was evacuated by helicopter.

Eduardo Jr. guided me 100 m. down the mountain to a bukal (spring) where potable water can be had. As can seen from discarded shampoo sachets, campers frequently bathe here. Also in the area are four bat-and-bird-inhabited tunnels built by the Japanese close to one another during the war. Birds panicked and flew away as we entered one guano-filled tunnel. It is said that campers caught by storms seek refuge here. The fifth and longest tunnel is located a distance away. A Japanese expedition had tried to enter it but retreated. And it remains unexplored to this day.

Upon our return, Mang Ed invited me to a late lunch, and we feasted, kamayan-style, on tuyo, fried egg and rice, washed down by mountain spring water. We left the campsite at around 2:30 PM. The descent was faster and less tiring, but slippery and harder on the joints. Along the way we passed and conversed with two groups of backpackers on the way up. Peak season has just began. We reached the Mountaineer’s store at around 4 PM, snacked on crackers and soft drinks, changed our clothes and left for Manila, passing by Lipa City and the towns of Malvar, Tanauan, Sto. Tomas and Calamba City before entering the South Luzon Expressway. We were home by 8:30 PM.