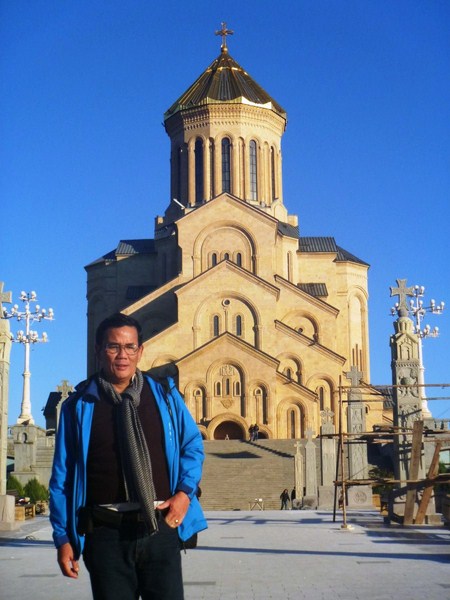

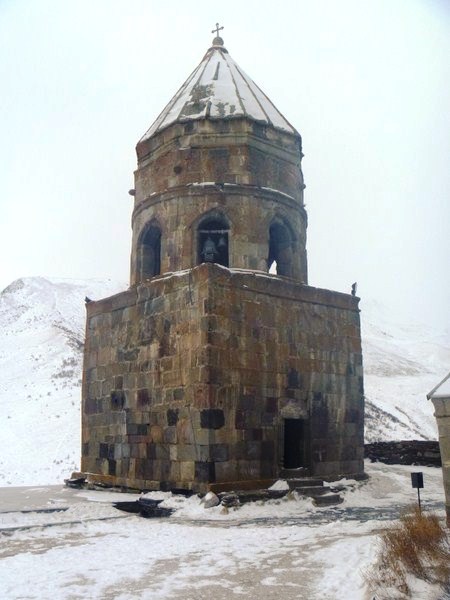

The highlight of my walking tour of Tblisi, with Filipina expat Ruby Bebita, was my visit to the very majestic Tsiminda Sameba Cathedral, a ready-made photo op also known as the Holy Trinity Cathedral of Tbilisi. The main cathedral of the Georgian Orthodox Church, it is the third-tallest Eastern Orthodox cathedral in the world.

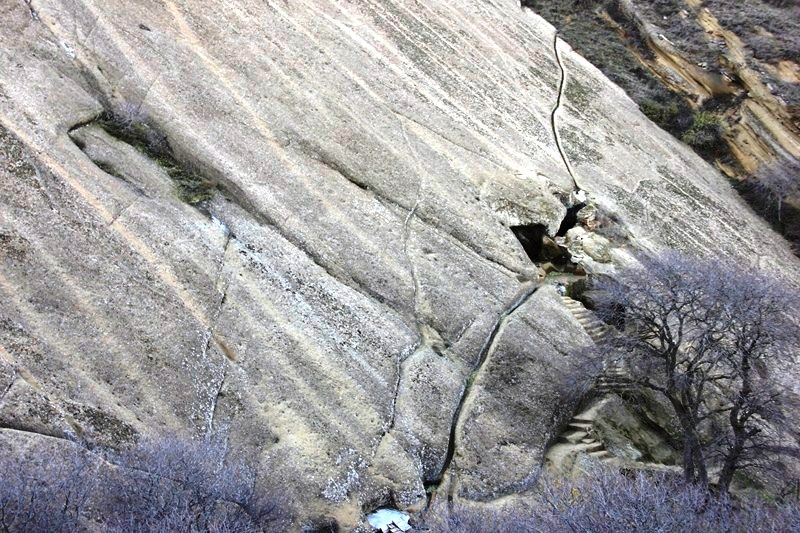

The cathedral, in the historic neighborhood of Avlabari in Old Tbilisi, was erected on Elia (St. Elijah) Hill, which rises above the left bank of the Kura River (Mtkvari). Getting there involved a steep, uphill climb.

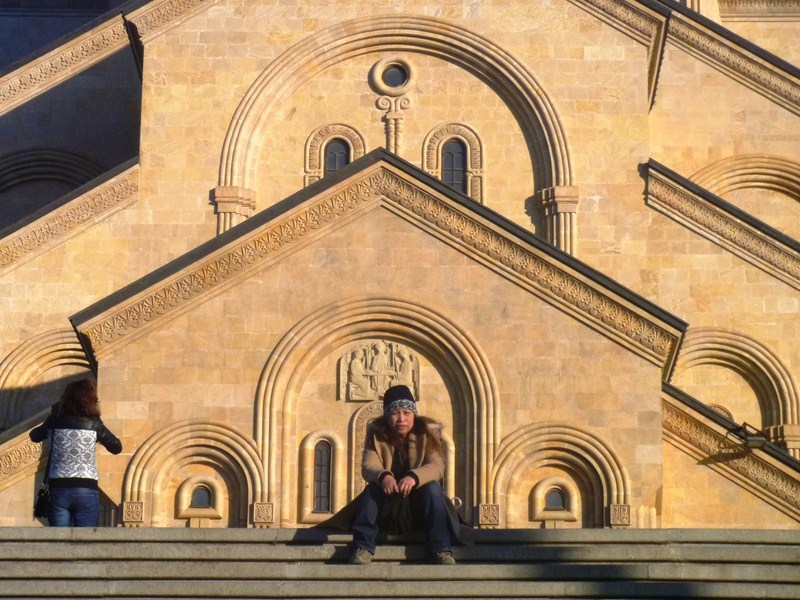

Though it has some Byzantine undertones, it was built in the traditional Georgian tetrahedron style of architecture, a synthesis of traditional styles which, at various stages in history, have dominated Classic Georgian church architecture. The Sameba complex consists of the main cathedral church, a free-standing bell tower, the Patriarch’s residence, a monastery, a clerical seminary, theological academy, several workshops, places for rest, etc.

A winning design of Architect Archil Mindiashvili, the main cathedral’s construction was mostly sponsored by anonymous donations from several businessmen as well as common citizens. The foundation of the new cathedral was laid on November 23, 1995. Nine years later, on November 23, 2004 (St. George’s Day), in a ceremony attended by leaders of other religious and confessional communities in Georgia as well as by political leaders, the cathedral was consecrated by Ilia II, the Catholicos Patriarch of Georgia, as well as high-ranking representatives of fellow Orthodox churches of the world.

The breathtaking cathedral’s exaggerated vertical emphasis is regarded as an eyesore by many but venerated by as many others. The cathedral has a cruciform plan. Its golden dome, over a crossing, rests on 8 columns and is surmounted by a 7.5 m. high, gold covered cross. The dome’s parameters, independent from the apses, imparts a more monumental look to the dome, and the cathedral in general.

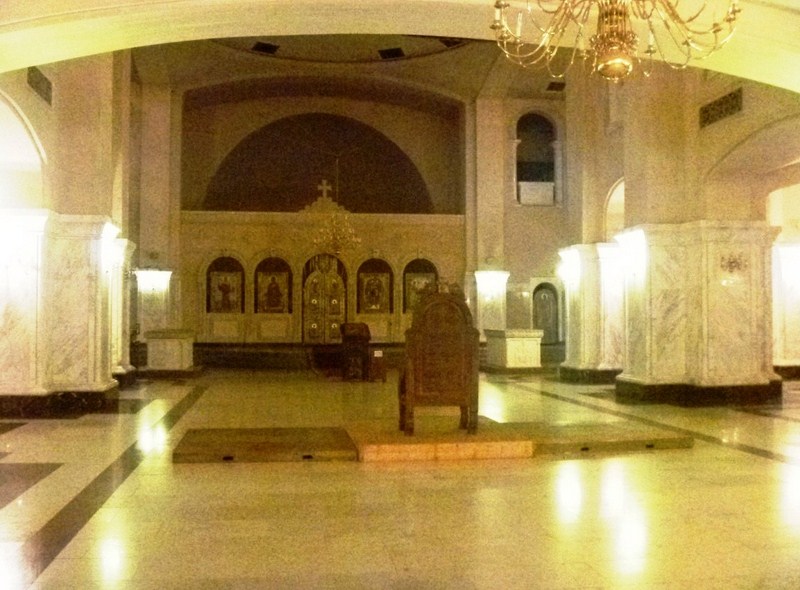

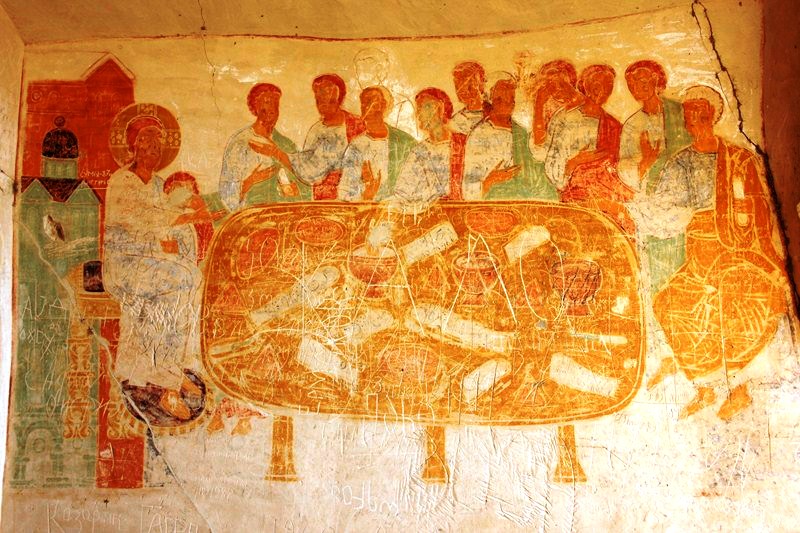

This cathedral consists of 9 chapels (the chapels of the Archangels, John the Baptist, Saint Nino, Saint George, Saint Nicholas, the Twelve Apostles, and All Saints); 5 of which are situated in a large, underground compartment. The cathedral, measuring 56 m. by 44 m., has an overall area (including its large narthex) of 5,000 sq. m., a volume of 137 cu. m. and an interior area of 2,380 sq. m. (it can accommodate 15,000 people). Its height, from ground level to the top of the cross, is 105,5 m.. The 13 m. high underground chapel occupies 35,550 cu. m..

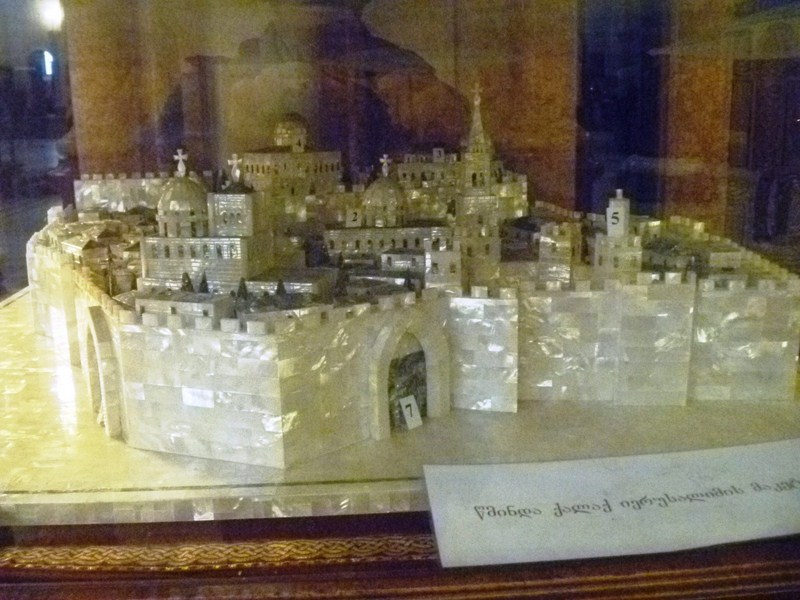

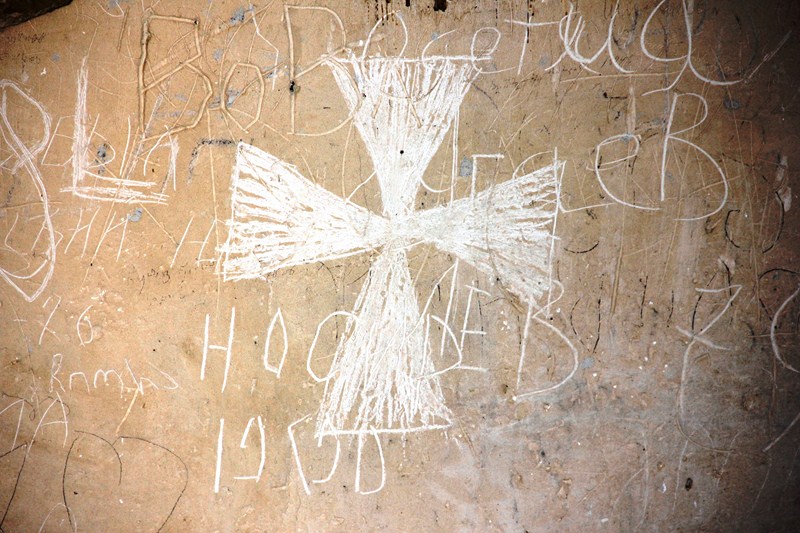

Natural materials were used for its construction. Marble tiles were utilized for the floor and the altar was decorated with mosaic. Its murals were executed by a group of artists guided by Amiran Goglidze. Though still without frescoes, many of the icons that adorn the walls are stunningly beautiful and the doors are carved with very beautiful images of the saints. There’s also a model of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Its free-standing, adjacent bell tower is also as grand as the cathedral itself. The well kept and tidy grounds are adorned with beautiful, well-manicured lawns, grass and colorful varieties of flowers

Though it lacks the charm of the traditional and historical churches, this lovely, really big and new cathedral is still grand in its modesty and spiritual. Seen from almost every view point in Tbilisi, it was built by sacrifice and determination. Truly, it deserves more than a visit. As it sits high up atop a hill, it also has a fantastic view of the city and is also beautiful to behold at night when it is bathed with state-of-the-art spotlights. The cathedral is especially packed with worshipers on Saturday nights, Sunday mornings and feast days.

How To Get There: The neighborhood is served by the Avlabari Metro Station.

Qatar Airways has daily flights from Diosdado Macapagal International Airport (Clark, Pampanga) to Tbilisi (Republic of Georgia) with stopovers at Hamad International Airport (Doha, Qatar, 15 hrs.) and Heydar Aliyev International Airport (Baku, Azerbaijan, 1 hr.). Website: www.qatarairways.com.