The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is the permanent home, of a continuously expanding collection of Impressionist, early Modern and contemporary art and also features special exhibitions throughout the year.

Overlooking Central Park, the site’s proximity to the park afforded relief from the noise, congestion and concrete of the city and nature also provided the museum with inspiration. In 2013, nearly 1.2 million people visited the museum, and it hosted the most popular exhibition in New York City.

Established in 1939 by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation (established in 1937, it fosters the appreciation of modern art) as the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. The museum adopted its current name in 1952, after the death of its founder.

In 1959, the museum moved, from rented space, to its current Modernist, distinctively cylindrical building, a landmark work of 20th-century architecture designed by Frank Lloyd Wright who experimented with his organic style in an urban setting.

It took him 15 years, 700 sketches, and six sets of working drawings to create the museum. The museum underwent extensive expansion and renovations in 1992 (when an adjoining tower was built) and from 2005 to 2008.

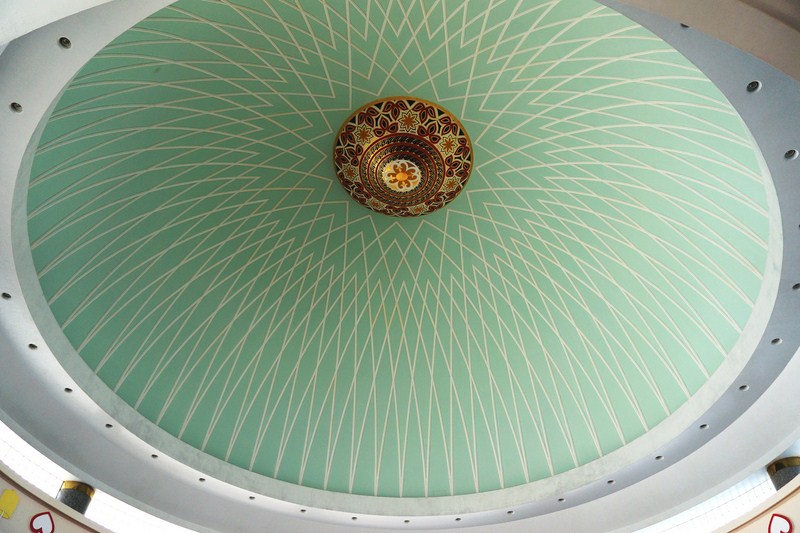

The building was conceived, by Rebay, as a “temple of the spirit” that would facilitate a new way of looking at the modern pieces in the collection.

The only museum designed by Wright and his last major work (he died six months before its opening on October 21, 1959), the appearance of the building, viewed from the street, is in sharp contrast to the typically rectangular Manhattan buildings that surround it (a fact relished by Wright).

It looks like a white ribbon curled into a cylindrical stack, wider at the top than the bottom, and displaying nearly all curved surfaces.

Internally, Wright’s plan for the viewing gallery was for the museum guests to ride to the top of the building by elevator, to descend, at a leisurely pace, along the gentle slope of the unique, continuous helical ramp gallery, extending up from ground level in a long, continuous spiral (recalling a nautilus shell) along the outer edges of the building and ending just under the ceiling skylight at the top.

The atrium of the building was to be viewed as the last work of art. The open rotunda afforded viewers the unique possibility of simultaneously seeing several bays of work on different levels and even to interact with guests on other levels.

Wright’s spiral design, embracing nature, with continuous spaces flowing freely one into another, also expresses his take on Modernist architecture’s rigid geometry.

To reduce the cost, the building’s surface was made out of concrete, inferior to the stone finish, with a red-colored exterior, that Wright had wanted and which was never realized.

Also largely for financial reasons, Wright’s original plan for an adjoining tower, artists’ studios and apartments also went unrealized until the renovation and expansion.

Wright’s carefully articulated lighting effects for the main gallery skylight had been compromised when it was covered during the original construction but, in 1992, was restored to its original design.

The “Monitor Building” (as Wright called it), the small rotunda next to the large rotunda, was intended to house apartments for Rebay and Guggenheim but, instead, became offices and storage space. In 1965, the second floor of the Monitor building was renovated to display the museum’s growing permanent collection.

With the 1990–92 restoration of the museum, it was turned over entirely to exhibition space and christened the Thannhauser Building, in honor of art dealer Justin K. Thannhauser, one of the most important bequests to the museum. Much of the interior of the building was restored during the 1992 renovation.

Also in 1992, a new, adjoining rectangular 10-storey limestone tower, taller than the original spiral and designed by the architectural firm of Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects, expanded the exhibition space with the addition of four additional exhibition galleries with flat walls.

Between September 2005 and July 2008, the museum underwent a significant exterior restoration to repair cracks and modernize systems and exterior details. It was completed on September 22, 2008. On October 6, 2008, the museum was registered as a National Historic Landmark.

In 2001, the museum opened the 8,200 sq. ft. (760 m2) Sackler Center for Arts Education (a gift of the Mortimer D. Sackler family), a facility located on the lower level of the museum, below the large rotunda.

It provides classes and lectures about the visual and performing arts and opportunities to interact with the museum’s collections and special exhibitions through its labs, exhibition spaces, conference rooms and 266-seat Peter B. Lewis Theater.

Beginning with Solomon R. Guggenheim‘s original collection works of the old masters since the 1890s, the museum’s collection (shared with the museum’s sister museums in Bilbao, Spain, and elsewhere) has grown organically, over eight decades. It is founded upon several important private collections. Here’s a chronology of the museum’s acquisitions:

- In 1948, the foundation’s collection included a broad spectrum of expressionist and surrealist works, including paintings by Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Joan Miró.

- In 1948, the collection was greatly expanded through the purchase of art dealer Karl Nierendorf’s estate of some 730 objects, notably German expressionist.

- In 1963, museum director Thomas M. Messer acquired a private collection from art dealer Justin K. Thannhauser for the museum’s permanent collection. These 73 works include Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and French modern masterpieces, including important works by Paul Gauguin, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, Vincent van Gogh and 32 works by Pablo Picasso.

- Artist Hilla von Rebay, its first director until 1952, also left, in her will, a portion of her personal collection of European avant-garde art, in particular abstract art that she felt had a spiritual and Utopian aspect (non-objective art), to the foundation, including works by Wassily Kandinsky, Klee, Alexander Calder, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian and Kurt Schwitters.

- In 1953, director James Johnson Sweeney acquired Constantin Brâncuși‘s Adam and Eve (1921), Paul Cézanne‘s Man with Crossed Arms (c. 1899) as well as works of other Modernist sculptors such as Joseph Csaky, Jean Arp, Calder, Alberto Giacometti and David Smith.

- The same year, the foundation also received a gift of 28 important works from the estate of Katherine S. Dreier, a colleague of Rebay and a founder of Société Anonyme, America’s first collection to be called a modern art museum. It included Little French Girl (1914–18) by Brâncuși, an untitled still life (1916) by Juan Gris, a bronze sculpture (1919) by Alexander Archipenko, three collages (1919–21) by German Hanoverian Dadaist Schwitters as well as works by Calder, Marcel Duchamp, El Lissitzky and Mondrian. Among others, Sweeney also acquired the works of Alberto Giacometti, David Hayes, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock.

- In 1991, Thomas Krens (director of the foundation from 1988 to 2008) acquired the Panza Collection, assembled byCount Giuseppe di Biumo and his wife, Giovanna. The collection includes examples of Minimalist sculptures by Carl Andre, Dan Flavin and Donald Judd, and Minimalist paintings by Robert Mangold, Brice Marden and Robert Ryman, as well as an array of Post-Minimal, Conceptual, and perceptual art by Robert Morris, Richard Serra, James Turrell, Lawrence Weiner and others, notably American examples of the 1960s and 1970s.

- In 1992, the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation donated 200 of Mapplethorpe’s best photographs to the foundation, an acquisition that initiated the foundation’s photography exhibition program. Spanning his entire output, it includes early collages, Polaroids, portraits of celebrities, self-portraits, male and female nudes, flowers and statues, mixed-media constructions and included his well-known 1998 Self-Portrait.

- In 2001, a large collection of the Bohen Foundation was gifted to the foundation. It consists of commissioned works of art (Pierre Huyghe, Sophie Calle, etc.), with an emphasis on film, video, photography and new media.

The building has been widely praised and inspired many other architects. However, the design polarized architecture critics who believed that the building would overshadow the museum’s artworks.

Some artists have also protested the display of their work in such a space. The continuous spiral ramp gallery, tilted with non-vertical curved walls, presented challenges to the museum’s ability to present art at all as it is awkward and difficult to properly hang paintings in the shallow, windowless concave exhibition niches that surround the central spiral.

Canvasses must be mounted raised from the wall’s surface. Paintings hung slanted back would appear “as on the artist’s easel.” There was also limited space within the niches for sculpture.

The slope of the floor and the curvature of the walls also combined to produce vexing optical illusions. Three-dimensional sculpture or any vertical object appears tilted in a “drunken lurch.”

To compensate for the space’s weird geometry, special plinths were constructed at a particular angle, so that pieces were not at a true vertical would appear to be so.

However, this trick proved impossible for an Alexander Calder mobile whose wire inevitably hung at a true plumb vertical, “suggesting hallucination” in the disorienting context of the tilted floor.

Some of the most popular and important art exhibitions held here include:

- The first season “Works and Process,” a series of performances at the Guggenheim begun in 1984, consisted ofPhilip Glass with Christopher Keene on Akhnaten and Steve Reich and Michael Tilson Thomas on The Desert Music.

- “Africa: The Art of a Continent” (1996)

- “China: 5,000 Years” (1998)

- “Brazil: Body & Soul” (2001)

- “The Aztec Empire” (2004)

- The Art of the Motorcycle– an unusual exhibition of commercial art installations of motorcycles.

- The 2009 retrospective of Frank Lloyd Wright – the museum’s most popular exhibit (since it began keeping such attendance records in 1992), it showcased the architect on the 50th anniversary of the opening of the building.

Dancers in Green and Yellow (1903, pastel and charcoal on tracing paper mounted to paperboard, Edgar Degas)

In The International, a shootout occurs in the museum. A life-size replica of the museum was built for this scene.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum: 1071 Fifth Avenue corner East 89th Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan, New York City, NY 10128, USA. Tel: +1 212-423-3500. E-mail: visitorinfo@guggenheim.org. Open 10 AM – 5:45 PM. Admission: US$25 for adults, US$18 for students and seniors (65 years + with valid ID), children below 12 years old is free.