On our way back to Manila with my son Jandy, friend Rainy Canillas and her daughters Tricia and Arianne, we noticed, from the main road, the sign for Museo Orlina and decided to make a stopover there.

The museum itself was hidden at the back, at the bottom of a short, but very intimidatingly steep and narrow road. Parking was not easy here. The museum is a just few meters across the Sta Rosa-Tagaytay road, near the rotunda. Landmarks are the Econo Hotel and the Balibago-Tagaytay jeepney terminal.

A showcase of the artistry of internationally-acclaimed and multi-awarded Ramon Orlina, the pioneer and foremost practitioner of glass sculpture in the country, Museo Orlina adds culture as part of Tagaytay City by exhibiting, to the delight and enchantment of art lovers and enthusiasts, superb and exultant body of works showcasing Ramon Orlina’s scintillating artistry.

The museum had its soft opening last December 2013 and formally opened its doors to the public on April 9, 2014.

Ramon Orlina, an architect by profession, had a late calling to sculpture. The “Father of Philippine Glass Sculpture,” he is best known for his abstract glass sculptures that use angles, illusions, and the fine lines and colors.

Orlina transformed glass by elevating it, from beyond the humble origin of its utilitarian, industrial function (drinking vessels, window glass panes, automotive windshields, etc.), to the dignity and respectability of art, producing unique works that have dazzled the art scene and placed the Philippines in the International Art Map.

His unique art pieces, ranging from 4-digit prices to multi million pesos each (the prices, though stiff, were befitting the work of a world class artist), are coveted, both locally and internationally, by avid art enthusiasts, numerous collectors and industrial designers and now grace finer homes, offices, commercial establishments and respected art galleries.

He is also a master in bronze sculptures and canvass pieces. His glass sculptures focused on slabs of thick, transparent glass with subdued colors (especially his hallmark deep green) and the glass is molded into some amazing shapes as well as some powerful moments.

Orlina’s second museum, the first being at his ancestral home in Taal, Batangas (Casa Gahol), this 4-storey modern, glass and concrete, box-type building, on a cliff, faces the Tagaytay Ridge, affording visitors a lovely vista of the famed Taal Lake and Taal Volcano.

The building is divided into two and has a number of galleries (all named after the artist’s daughters) – Reflections & Naesa Gallery (Level 1, an exhibition area for up and coming artists), Ningning Gallery (Level 2) and Anna Gallery (Level 3).

When visitors arrive, they are usually shown a short, 15-min. video introduction before going into the museum. It narrates how Orlina started this museum and how he himself got into glass sculpture and his other forms of creative works. We skipped this. Flash photography and video taking is prohibited. The staff was nice and friendly.

Too bad Mr. Orlina was having an afternoon nap when we arrived (his office doubles as his bedroom when he pulls down his Murphy bed). It would have been nice to meet and talk with him as I appreciated, up close and personal, the masterpieces of this renowned and exceptionally talented artist.

My exploration of the exhibits took one hour. or senior citizens, persons with disability and pregnant women, there’s an elevator going from floor to floor.

All of Orlina’s artworks here are only for display, except for a room where artworks (most of which are Orlina’s works and some renowned artists), while on display, are also available for public auction.

The lovely and interesting glass sculptures on display, many placed along the windows fronting Taal Lake, are made in different colors and hues of glass and crystals (pink, yellow, orange) and each piece tells an interesting story.

The glass sculptures are interspersed with jewelry, art cars, chairs and photographs of the artist’s works abroad as well as pieces made from a variety of mediums such as bronze and wood.

The quite informative exhibits have nameplates and a short explanation of the art piece.

One of my favorites is the two dimensional glass sculpture of Virgen Maria, a woman’s head that looks different from various angles. From the back angle, if you look at the sculpture’s eyes, you are given the illusion that they follow and watch you as you move.

The UST (Orlina is a University of Sto. Tomas Architecture graduate) quadricentennial sculpture, supposedly one of Orlina’s most expensive art works, displays bronze studies including a face bronze sculpture of Piolo Pascual, the artwork’s male model.

Framed artworks, sketches and chairs from other renowned Philippine artists such as Juvenal Sanso, Elmer Borlongan, Ann Pamintuan, Bencab (Benedicto Cabrera), Federico Alcuaz, Napoleon Abueva and other Philippine art masters were also on exhibit.

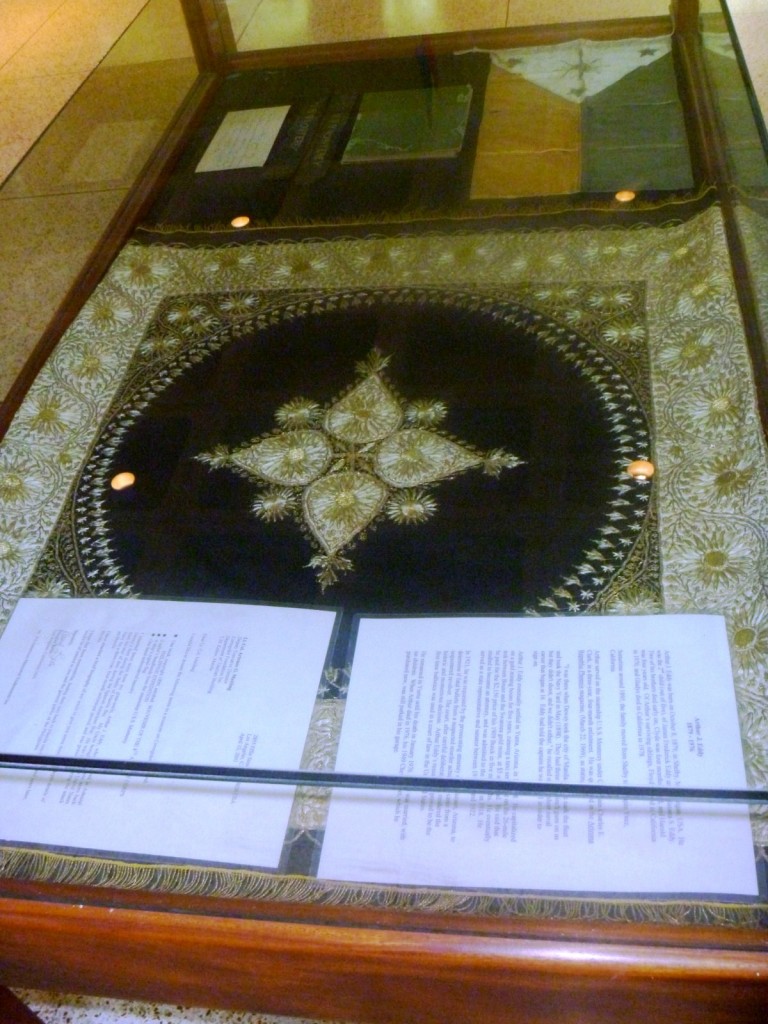

The Art of Isabelo Tampinco, made possible by a loan to the museum from the collection of Ernie and Chichi Sales, was ongoing at the Reflections Gallery.

The roof deck, with its breathtaking view of Taal Volcano, has a coffee shop which was closed during my visit.

Stairs located at the back of the stage lead you to a garage where you will find a vintage, red and white Volkswagen Beetle, aptly called Sabel, which is rented out as a bridal car.

Fully-restored, and retrofitted and accessorized, it has a ref; champagne and glass holders; dividing in-door windows and leather seats; and its body is painted with artwork, inspired by the taong grasa (literally translated as “oily person,”- meaning “homeless and dirty”) by fellow Kapampangan and National Artist Benedicto Cabrera (Bencab).

There’s also a fully restored, vintage Volvo, owned and accessorized by Orlina, with an interesting cubist-abstract hue. Orlina’s signature colors of orange, green, white and blue are painted, in a Piet Mondrian-linear style, all over the car’s body.

At the ridge side is an amphitheater where plays, events, and other special occasions can be held for a fee.

There’s also an outdoor Sculpture Garden with art piece installations. While, taking a leisurely walk through the exhibit, visitors can also enjoy the Tagaytay breeze and the ridge view.

The quaint, clean and well-maintained Museo Orlina, a cultural indulgence where one may get to appreciate awesome art pieces and works from one of the country’s renowned artists, adds a certain refined and cultured option for Tagaytay visitors and weekend residents who are looking for something unique while enjoying the cooling breeze and lake vista.

Museo Orlina: Hollywood Subdivision Rd., Hollywood Subd., Brgy. Tolentino East, Tagaytay City, Santa Rosa – Tagaytay Rd., Tagaytay, Cavite. Open Tuesdays to Sundays, 10 AM – 6 PM. Tel: (046) 413 2581. Mobile number: (0995) 735-4462. E-mail: info@museo-orlina.org. Website: www.museo-orlina.org. Admission (includes guided tour): general (PhP100), students and senior citizens with valid ID (PhP80. Manila office: Orlina Atelier. Tel: (02) 781-5918 and 781-9471. Fax: (02) 749-6439. Mobile number : (0917) 880-5108. E-mail: orlina@pldtdsl.net. Website : www.orlina.com.