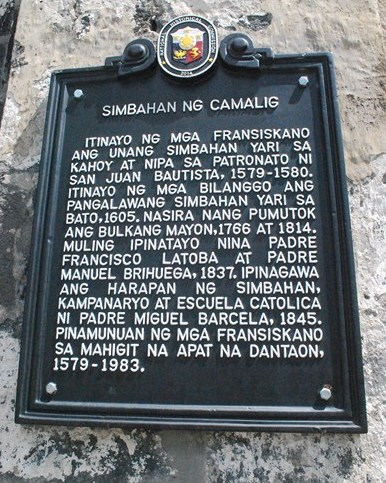

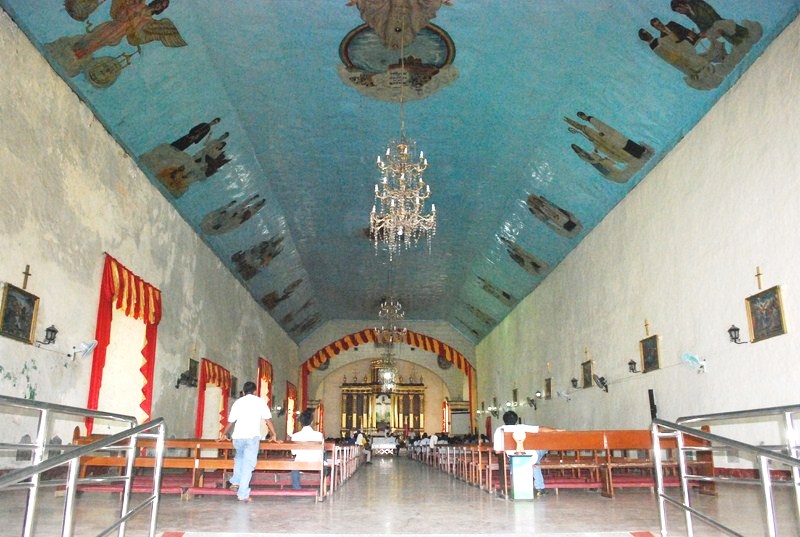

First built by Franciscan Fr. Pedro de Alcareso in 1616, the present structure, built by secular clergy, was completed in a period of 16 years (1864-1879). The stately Baroque-style church was declared as a National Landmark on August 1, 1973 by virtue of Presidential Decree No. 260 and amended by Presidential Decree No. 1505 on June 11, 1978.

The church was also one of the only two declared sites in Bicol Region that were categorized by the National Museum of the Philippines as a National Cultural Treasure of the country. Its marker was unveiled on June 22, 2012.

The church, built with dark volcanic soil and stones found in the area, has an unusual floor plan with inexplicable compartments and walls with stones bearing mason marks, rarely seen in the Philippines. The beautiful bell tower, embedded with Rococo designs, has rocaille elements and a beautiful and unique tower clock.

City Mayor’s Office: Poblacion, Tabaco City 4511, Albay. Tel.: (052) 487-5200

How to Get There: Tabaco City is located 558 kms. from Manila and 21 kms. (a 45-minute drive) northeast of Legaspi City.