From the Philippine Tarsier and Wildlife Sanctuary, we returned to our airconditioned coach and proceeded, via the Tagbilaran City-Corella-Sikatuna-Loboc Rd., on our 14.5-km./15- min. drive to Loboc where we were to have a late lunch while cruising the Loboc River. We arrived at the Loboc Tourism Complex by 1:30 PM. Across the complex is the Church of St. Peter the Apostle, the second oldest church in Bohol and its first declared National Cultural Treasure. Built in 1602 by Fr. de Torres, it was destroyed by fire in 1638. The present church was built in 1734.

The church I saw was just a broken shell of what I saw 11 years ago as the church sustained major damage during the devastating October 15, 2013, 7.2 magnitude earthquake. Its Early Renaissance façade was completely destroyed while major damage could be seen at the lateral walls and ceiling of the church as well as its convent. The whole church has been fenced in as its collapsed middle section cannot be entered at all. The pipe organ was said to among the elements of the church that were spared from damage.

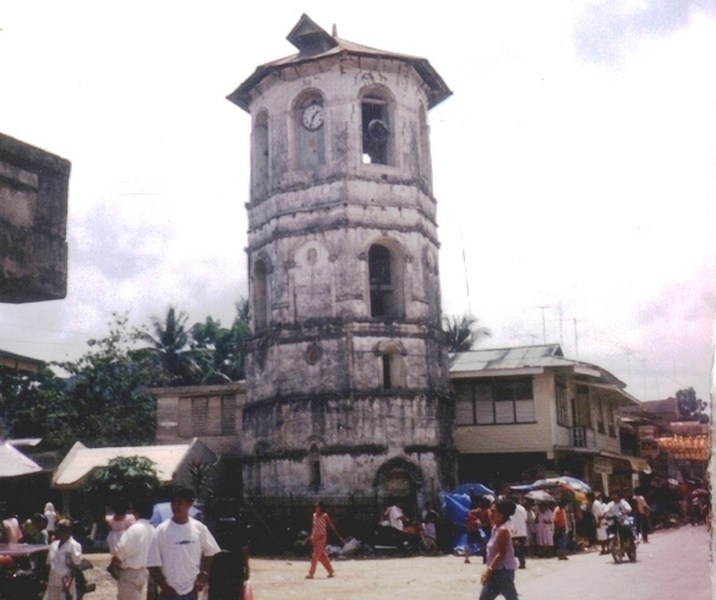

Its separate 21-m. high, 4-storey octagonal stone bell tower, located about 30 m. (98 ft.) across the street from the church, also collapsed leaving less than half the tower standing. Years ago, the timely objection by the Lobocnons prevented the bell tower’s destruction when a huge concrete bridge, not justified by any traffic, was being built.

At that time, the townspeople had expressed their apprehension that driving the piles to support the ramp, from the superstructure to ground level, might destroy the church, the belfry or both.The project was thus discontinued and this unfinished white elephant of a bridge, that stuck out like a sore thumb in the town center, has somehow been put to good use, having been converted, in 2008, into the Alfonso L. Uy Promenade. Sadly, what man failed to destroy, nature almost succeeded in doing.

To turn the bridge into a promenade, Arch. German Torero, a National Commission on Culture and the Arts (NCCA)-accredited architect, was tasked to carefully design it so that it will blend with the design of the nearby church and bell tower. Some PhP4 million in corporate funds was also spent to install tiles, build a stairway on the Poblacion side and adding enhancements. Today, the promenade, now a tourist attraction, is used as a park as well as viewing platform to see the damaged (and, hopefully, soon to be repaired) church and bell tower