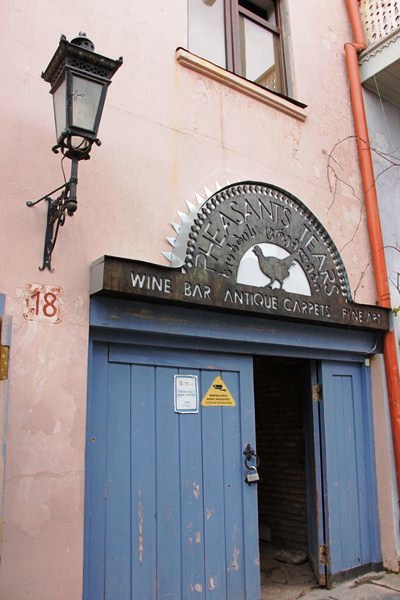

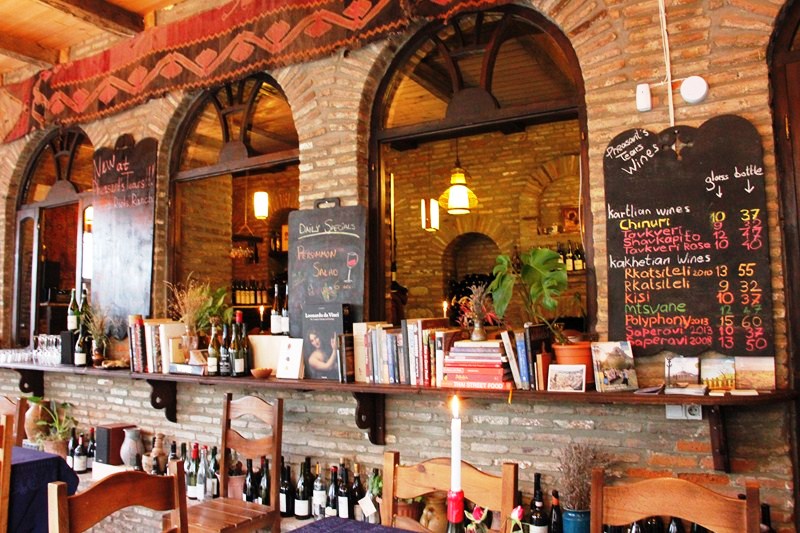

After lunch at Pheasant’s Tears in Sighnaghi, Buddy, Pancho, Melissa, Riva, our guide Sopho and I continued on the final leg of our 3-day, GNTA-sponsored Georgian Countryside Tour, a 50-km./40-min. drive to the village of Tsinandali in the Kakheti region (79 kms. east of Tbilisi).

The village, lying in the Alazani River valley, was inherited by the 19th century aristocratic poet (considered to be the founder of Georgian romantic poetry), writer, military leader, diplomat, public figure and inventor Alexandre Chavchavadze (1786-1846), one of the most important figures of his time, from his father, Prince Garsevan Chavchavadze.

Alexandre refurbished the estate, constructed a new Italianate palace and, in 1835, built a decorative garden, a tranquil refuge in the shadow of the dramatic neighboring Caucasian Mountains. Here, he frequently entertained his foreign guests with music, wit and, most especially, the fine vintage wine made at his estate winery (marani), Georgia’s oldest and largest.

Familiar with European ways, Alexandre combined European and centuries-long Georgian winemaking traditions when he built the winery in 1846. He died in a bizarre accident in Tbilisi when his cloak got caught in the wheel of his carriage and he was thrown out, hitting his head on the ground.

Alexandre’s vineyard is still cultivated to this day and the highly regarded dry white Tsinandali is still produced here. Visitors can see a bottle of Saperavi wine from 1839, the first harvest at Tsinandali, plus a unique collection of 16,500 bottles of other sorts of wines from many countries.

On February 8, 1886, after David Chavchavadze’s (Alexandre’s son) death, the Chavchavadze family estate and park were acquired by the Estate Department of the Russian Empire and passed to the property of Tsar Alexander III and the Imperial family due to the failure to pay the debt to the Russian Public Bank.

David had to mortgage the house to raise 14,000 silver rubles as ransom for the 23 women and children (including his wife and children) as well as servants of the household kidnapped on September 1854 by the charismatic Muslim leader Imam Shamyl and his Lezgin tribesmen from the Dagestan mountains.

In 1887, the Tsinandali garden was renovated and, in 1917, was passed to the state. On August 1, 1947, the estate was organized into a museum and, in 2008, underwent renovation works when its rooms were restored with 19th century furnishings.

The 18-hectare house-museum, now leased to the Silk Road Group, a Georgia-based company, often hosts various exhibitions of works of various prominent Georgian and foreign artists such as Salvador Dali, Elene Akhvlediani, Levan Mekhuzla, Dimitri and Sandro Eristavi, Sergo Kobuladze and Karlo Kacharava. Each season, new exhibits make museum even more attractive, turning it into an important cultural site.

The perfect mixture of Georgian and European architectural cultures, this relatively small and unpretentious, 2-storey manor house, made with local sandstone, symbolizes the values Aleksandre Chavchavadze wanted to establish in Georgia. The exterior facade features unusually fine stonework and a veranda that incorporates Eastern ornamental woodwork and decorative elements that wraps around two sides of the house.

The rectangular house is situated in the midst of a beautiful and serene 18-hectare park. Its unique and interesting layout features a mixture of natural and decorated gardens. The first landowner in Georgia to employ European landscape designers, Alexandre had the park was renovated in 1887 by the famous landscape designer Arnold Ragel.

The park, a harmonious synthesis of wilderness and decorative landscapes, incorporates a number of existing oak, lime and maple trees (now 400 to 500 years old) and consists of orchards, walks and paths lined with vines, flowerbeds, and traditional Georgian rose bushes. On August 20, 1987, the Georgian government placed Tsinandali park on the list of the National Monuments of Landscape Architecture.

We arrived at the estate just before closing time, parking along a driveway flanked by superb sentinels of cypress trees. From the imposing iron entrance gate, we walked toward the house, anxious to get away from the biting cold. Upon entering, we were met by our English-speaking Georgian guide who directed us, up the grand stairway, to the second floor where we were to explore nine rooms of the house that show what the good life in Kakheti must have been like in the 19th century. The exhibits, exclusively devoted to Alexandre’s memorabilia and that of his family, were captioned in Russian and Georgian only.

Our guide showed us objects that represent both the poet’s life and creative work – his epistolary and iconography archive; editions on various subjects in French, German, English, Polish and Armenian languages; manuscripts; works of photographer Ermakov; samples of painting and lithography; household objects; crockery (Chinese, Japanese, French, German, Italian, Georgian, Russian) and musical instruments.

The museum still had some of its original Georgian, Russian and French furniture, including the French piano (the first recorded piano in Georgia) with a folding keyboard, bought from Europe and given by Alexander Griboedov to his wife Nina (Alexandre’s daughter). There were also interesting paintings and photos of people and events associated with the house, including the Lezgin raid. There’s also a reproduction of the Winterhalter portrait of Chavchavadze’s wife Salome. Photography wasn’t allowed inside.

There is a souvenir shop on the ground floor of the museum where one can find arts and crafts from the Kakheti region. Copies of Nino Chavchavadze’s handkerchief and of artifacts from archaeological excavations in Georgia are among the items for sale. Before leaving, we had coffee at the museum’s café.

Tsinandali Museum: 2217 M-42, Tsinandali, Telavi District. Tel: (+995, 350) 3 37 17. Mobile number: (+995 5 99) 71 41 22. E-mail: maia_kokocha@yahoo.com. Website: www.tsinandali.com. Open Mondays to Thursdays, 10 AM – 6 PM, Fridays to Sundays, 10 AM – 7 PM. During the winter months, the museum closes at 5 PM.

Admission: standard (5 GEL, includes entrance to the garden, museum and vineyard as well as a guide to the museum exhibits), standard + tasting of one sort of Georgian wine (7 GEL), standard + tasting of various Georgian wines (20 GEL), visiting only park (2 GEL), schoolchildren (3 GEL) and university/college students (4 GEL). Entrance is free on May 18 (International Museum Day). Admission is also free for “Museum Honored Guests,” ICOM & UNESCO, children under school age and socially deprived, and refugees.

Georgia National Tourism Administration: 4, Sanapiro St, 0105, Tbilisi, Georgia. Tel: +995 32 43 69 99. E-mail: info@gnta.ge. Website: www.georgia.travel; www.gnta.ge.

Qatar Airways has daily flights from Diosdado Macapagal International Airport (Clark, Pampanga) to Tbilisi (Republic of Georgia) with stopovers at Hamad International Airport (Doha, Qatar, 15 hrs.) and Heydar Aliyev International Airport (Baku, Azerbaijan, 1 hr.). Website: www.qatarairways.com.