The “Rice, Biodiversity and Climate Change” Exhibit, inaugurated last December 17, 2013, is the National Museum of Anthropology’s third permanent exhibit and is part of the celebration of the National Year of Rice for the Philippines led by the Philippine Rice Research Institute (PhilRice) and the Department of Agriculture (DA) and was supported by Senator Loren Legarda, Chairperson of the Senate Committee in Climate Change.

Check out “National Museum of Anthropology”

It aims to create more appreciation on rice, its connection with other ecosystems, and how the changing climate affects rice production and highlights the need to address biodiversity loss and climate change in relation to rice production.

The exhibit also highlights, among others, the history of rice cultivation in the Philippines, rice farming practices, plants and insects in the field, farmers` way of life, and the importance of rice conservation.

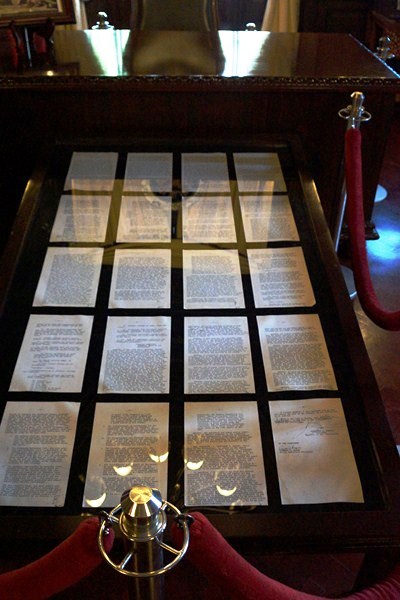

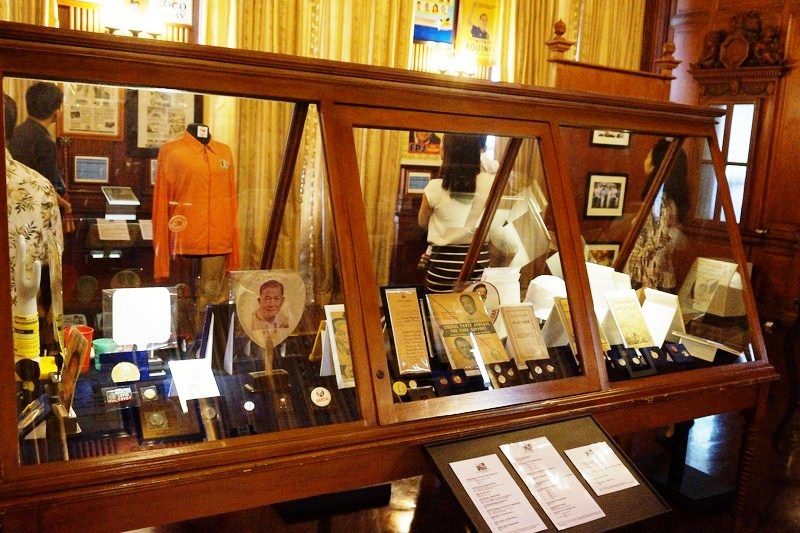

Displayed are varieties of rice grains, from the National Museum of the Philippines and PhilRice, still in panicles along with artifacts, flora and fauna specimens and photographs.

There are also numerous tools used in farming and the religious aspect of farming such as the barrel-shaped mortar (luhong) and pestle used for pounding husked rice, grains and root crops; harrow and plow as well as funnel-shaped locust baskets (made of bamboo, rattan and nito, with a wooden side handle), bulol (anthropomorphic wooden rice deity central to the Ifugao rice culture); and minarigay or marigay (rice containers).

Also on display are different art pieces that feature rice such as the water buffalo (carabao)) figure by Mariano Edjawan and “Planting Rice”, a 3 cm. by 33 cm. oil on canvas painting by Norris Castillo. The 0.64 cm. by 0.95 cm. “Harvesting,” another oil on canvas painting by Norris Castillo, can only be seen with the help of a magnifying glass.

“Rice, Biodiversity and Climate Change” Exhibit: Antonio and Aurora Tambunting Hall, 4/F, National Museum of Anthropology, Agrifina Circle (or Teodoro Valencia Circle, adjacent to the National Museum of Fine Arts building),Padre Burgos Drive, Rizal Park, Ermita, Manila. Tel: (02) 8528-4912 and (02) 8527-0278. E-mail: nationalmuseumph@gmail.com. Open Tuesdays to Sundays, 10 AM – 5 PM. Admission is free.