From Piazzale Michangelo, a five minute stroll up took us to the unique and beautiful Basilica of San Miniato al Monte (St. Minias on the Mountain), a basilica standing atop Monte alle Croci, one of the highest points in the city. One of the most scenic churches in Italy, it absolutely has the best view of the city.

Here, we could see the Duomo and Palazzo Vecchio up to the last standing parts of the medieval walls that once surrounded Florence. A stunning example of original Tuscan Romanesque architecture, it has been described as one of the finest Romanesque structures in Tuscany.

Check out “Palazzo Vecchio“

Here are some trivia regarding the basilica:

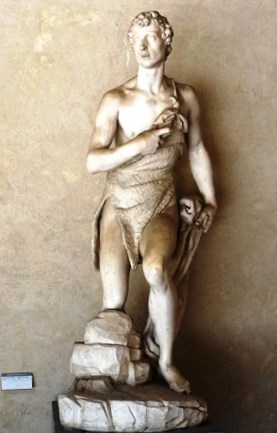

- The church is dedicated to Miniato or Minas, an Armenian prince or Greek merchant who once served in the Roman army under Emperor Decius. Miniato was denounced as a Christian after becoming a hermit. He was brought before the Emperor, who was camped outside the gates of Florence, and was ordered to be thrown to the beasts in the amphitheater. A panther refused to devour him so, in the presence of the Emperor, he was beheaded. Miniato was alleged to have picked up his head, put it back on his shoulders, crossed the Arno and walked up the hill of Mons Fiorentinus, to his hermitage. A shrine was later erected at this spot and, by the 8th century, there was already a chapel built there.

- The basilica served as an important setting in Brian de Palma’s 1976 filmObsession.

- On June 16, 2012, Dutch royalPrincess Carolina of Bourbon-Parma married businessman Albert Brenninkmeijer

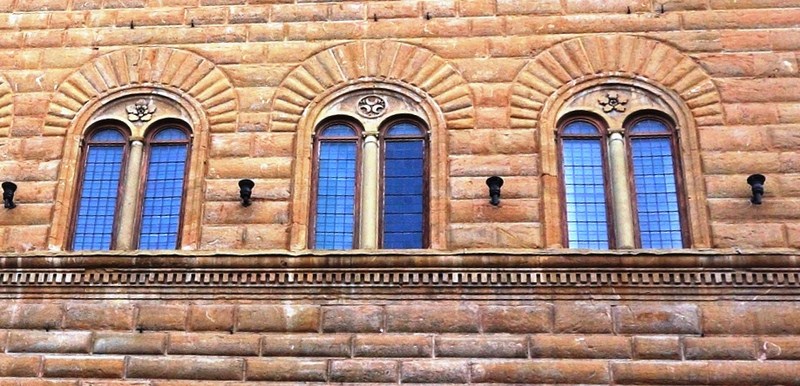

The present church, built on the site of a 4th century chapel, was started in 1013 by Bishop Alibrando (Hildebrand) and was endowed by the Emperor Henry II. The green (from Prato) and white (from Carrara) marble façade, with strict geometric patterns similar to the facades of Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella, is the most important element of the façade.

The facade was probably begun in about 1090 although the upper parts date from the 12th century or later. It was financed by the Florentine Arte di Calimala (the eagle that crowns the façade is their symbol), a cloth merchants’ guild who, from 1288, were responsible for the church’s upkeep.

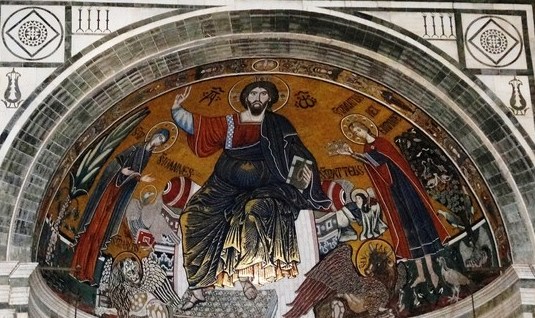

The lower part of the facade is decorated by fine arcading. A fine 12th century mosaic of Christ enthroned between the Madonna and St. Miniato, over a central window, decorates the simpler upper part of the facade.

The campanile, which collapsed in 1499, was replaced in 1523 although it was never finished. In 1530, during the siege of Florence, it was used as an artillery post by the defenders. To protect it from enemy fire, Michelangelo had it wrapped in mattresses.

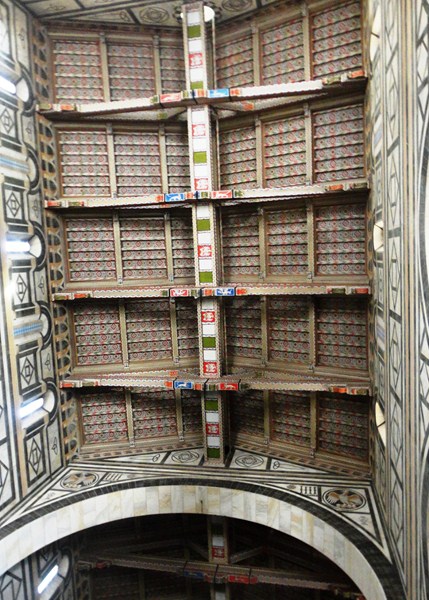

The tripartite Romanesque interior of the basilica, little changed since it was first built, has three naves (without a transept); a trussed timber roof and ceiling (decorated in 1322) in the central nave; and exhibits the early feature of a choir, elevated on a platform above the large crypt (the oldest part of the church).

Fragments of 13th and 14th century frescoes by Taddeo Gaddi (1341) may be seen in the vaults of the crypt. Finished about 1062, the austere crypt is divided into 7 small aisles by 38 slender columns that were decorated “in gold” by Gaddi in 1342. Enclosed by a marble column fence and elaborate wrought-iron gate (1338), this vast space contains an impressive 14th century wood chorus.

Columns, with alternating polystyle pilasters, divide the naves. The side (lateral) naves were finished in 1070. The patterned pavement, in the central aisle, dates from 1207 and includes marble intarsias representing the signs of the zodiac and symbolic animals.

The beautiful, freestanding Cappella del Crocefisso (Chapel of the Crucifix), designed by Michelozzo in 1448, dominates the center of the nave. It originally housed the miraculous crucifix, now in Santa Trìnita, and is decorated with panels long thought to have been painted by Agnolo Gaddi. Luca della Robbia or his family did the delicate glazed terracotta decoration of the vault (the crucifix above the high altar is also attributed to him) while the mosaic of Christ between the Virgin and St Minias was made in 1260.

The 11th century high altar supposedly contains the bones of St. Minias himself (although there is evidence that these were removed to Metz before the church was even built). The intimate raised choir, with its fine inlaid wooden choir stalls, and the presbytery contains a magnificent Romanesque ambo (pulpit) and screen, both made in 1207. The lectern is supported by a “column” composed of a lion, a monk-telamon and an eagle with outstretched wings.

Mosaic o the Blessing Christ, the Pantocrator, flanked by the Madonna, St. Minias and the symbols of the four Evangelists

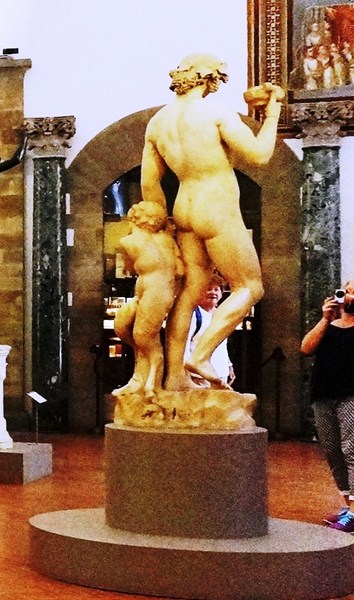

The bowl-shaped vault of the apse (c. 1260) is dominated by a great mosaic, dating from 1297, of the Blessing Christ, the Pantocrator, flanked by the Madonna, St. Minias and the symbols of the four Evangelistswhich depicts the same subject as that on the façade and is probably by the same unknown artist.

The figures stand out Byzantine-style against a gold background in a field populated with oriental birds (symbolizing souls). The date palm, on the left, symbolizes Christ Resurrected, while the phoenix on the right, spouting flames from its beak, and the peacock on the left, both symbolize the Resurrection of Christ.

The great fresco cycle on the 16 stories of the Life of St. Benedict (taken from “Dialogues” of Gregory the Great and from “Golden Legend” by Jacopo da Varagine), illustrated in chronological sequence (almost like a film) by Spinello Aretino (1387-88), decorates the entrance of the sacristy, to the right of the presbytery. The first undertaking of the Olivetans, it was commissioned by Benedetto degli Alberti.

On the left of the nave, stairs lead to the Chapel of St. James or Chapel of the Cardinal of Portugal (Cappella del Cardinale del Portogallo), a collaboration of outstanding artists of Florence. One of the most magnificent funerary monuments of the Italian Renaissance, it was designed by Brunelleschi’s associate, Antonio Manetti (but finished, after his death in 1460, by Antonio Rossellino in 1461).

Madonna with the Child and Saints Francis, Mark, John the Baptist, John the Evangelist, James and Anthony Abbot

It was built by the Alberti workshop of Antonio and Bernardo Rossellino in 1473 as a memorial (the only tomb in the church) to Cardinal James of Lusitania, the Portuguese ambassador in 1459, who died in Florence on August 27, 1459. The chapel was decorated by Alesso Baldovinetti, Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo. The 5 splendid roundels representing the Holy Spirit and the Cardinal Virtues are by Luca della Robbia (1461-66).

A fine cloister, adjacent to the church, also designed by Bernardo and Antonio Rosselino, was planned as early as 1426, financed by the Arte della Mercantia of Florence and built from 1443 to the mid-1450s. The fortified bishop’s palace, to the right of the church, was the ancient summer residence of the bishops of Florence from 1295- 1320. It was later used as a a convent, barracks, a hospital and a Jesuit house.

Defensive walls, originally built hastily by Michelangelo during the 1529-30 siege and expanded into a true fortress (fortezza) by Cosimo I de’ Medici in 1553, surround the whole complex and now encloses the Porte Santea, a beautiful, monumental cemetery laid out in 1854. Carlo Collodi (creator of Pinocchio), Giovanni Spadolini (politician), Pietro Annigoni (painter), Luigi Ugolini (poet and author), Mario Cecchi Gori (film producer), Libero Andreotti (sculptor), Maria Luisa Ugolini Bonta (fine artist), Marietta Piccolomini (soprano), Giovanni Papini (writer) and Bruno Benedetto Rossi (physicist) are buried here.

When ascending the stairs of the basilica, the adjoining Olivetan monastery can be seen to the right. It began as a Benedictine community but was then passed to the Cluniacs and, finally, in 1373, to the Olivetans who still run it. The monks here still make their famous tisanes (herbal tea), liqueurs and honey which are sold to visitors from a shop next to the church.

Basilica of San Miniato al Monte: Via delle Porte Sante, 34, 50125 Florence, Italy. Tel: +39 055 234 2731. Open daily, 9:30 AM -1 PM and from 3 – 7 PM; Sundays 3 – 7 PM. Visit the church on Sundays and feast days as the monks accompany Mass in the crypt with Gregorian chant at 10 AM and 5.30 PM. During week days, the Gregorian chant takes place at 5:30 PM in summer. This time might change to 4:30 PM in winter.