After lunch at Liliw Fast Food, I took advantage of a lull in the rain and walked up the road towards the town’s red brick and adobe Church of St. John the Baptist. This church was first built in wood in October 1620, rebuilt in stone from 1643 to 1646 but was partially destroyed during the July 18, 1880 earthquake. The church and convent were reconstructed in 1885 but partially burned on April 6, 1898.

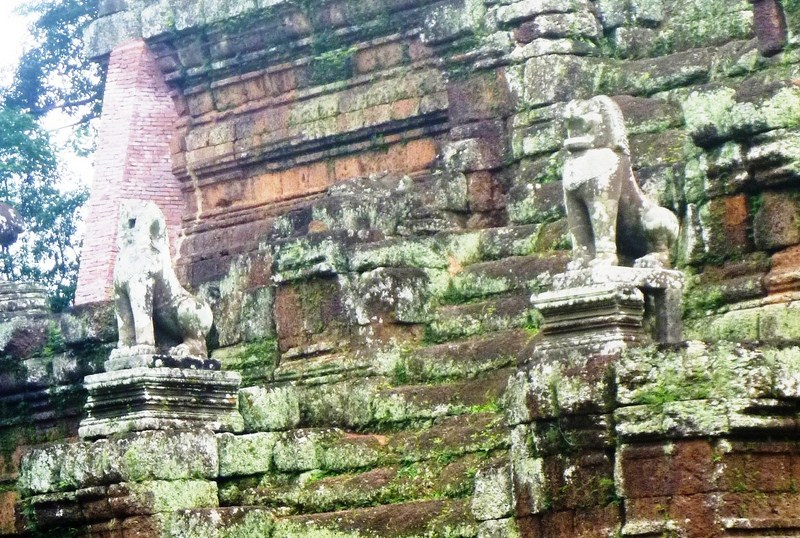

The church’s elegant, 3-level Baroque-style facade, divided by superpositioned columns into 7 segments and extending up to the pediment, has a semicircular arched main entrance finished with irregularly cut block of stones surmounted by layers of bricks, a bas-relief depicting the Baptism of Christ by St. John the Baptist on the second level and a centrally located statued niche on the undulating pediment.

On the right is the immense, moss-covered, 3-storey bell tower covered by a dome and topped by a tower. It has a good view of Laguna de Bay. Inside the church are retablos (altar backdrops) finished in gold leaf. The 4-level retablo mayor (main altar) at the center contains 13 niches housing statues of saints. The center of the lowest level contains the tabernacle. The two side retablos houses 4 niches of saints. A stained glass dome is located above the main altar. Regretfully, the ceiling of red brick and mahogany-finished wood was painted white.

Before leaving, I entered a small passageway to the left of the main entrance to visit the Capilla de Buenaventura, a small chapel dedicated to Franciscan Fr. Pedro de San Buenaventura, author of Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala, the first Tagalog dictionary which was printed in Pila, Laguna in 1613. His image is enclosed in a glass case which is believed to be 500 years old. Here, I lighted a bundle of 7 multi-colored candles which I bought for PhP40. On the right side of the church’s entrance is the church’s Perpetual Adoration Chapel.

The church’s grounds, developed to promote Christian teachings for pilgrims, has a patio with a white-painted statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus flanked by several whitewashed statues of different saints, the child Jesus and the Virgin Mary.

Church of St. John the Baptist: Poblacion, Liliw 4004, Laguna. Tel: (049) 563-3511 and (049) 234-1031.

How To Get There: Liliw is located 110 kms. from Manila and 17 kms. from Sta. Cruz.