I again got an invitation, from Mr. Pete Dacuycuy, to join a media familiarization tour of another Bluewater resort (the first one we visited was the Panglao Bluewater Resort in Bohol), this time to Sumilon Bluewater Island Resort. Joining me was fellow Panglao visitor Ms. Ma. Joy Elaine C. Felizardo (www.gastronomybyjoy.com) and Ms. Lara Louise Gabrielle L. Antonio (Editorial assistant at Mabuhay Magazine) plus Mr. Jimbo Owen B. Gulle (Editor-in-chief of Powerplay Magazine); Ms. Ma. Katrina Camille Cabanos (ZALORA Philippines); Ms. Liana Kathleen Smith-Bautista (www.liveloveblog.com); and Ms. Risa Halaguena and Ms. Rachelle Elaine Mapa (Account Manager), both from Essential Philippines Magazine.

We all arrived at Sibulan Airport (Negros Oriental) by 3:30 PM via a PAL Express flight. Upon exiting the terminal, we were whisked, via two airconditioned vans, to Sibulan Port where a big 50-pax outrigger boat (Jeffrey) was waiting to bring us to the island. Normally, to get to the island, visitors usually make a 20-min. land trip to Tampi port, then ride a fast craft going to Oslob on Cebu Island.

From Oslob (a 3-hour drive from Cebu City), they then make a 10-min. land trip to Bancogon Pavilion, where the private ferry port going to Sumilon Bluewater Island is located. The free 2-way transfers between the the pavilion and Sumilon Island are scheduled at 1.5 hr. intervals with the first trip at 7 AM and the last at 4:30 PM. We were to forego this tedious land-sea transfer and, instead, directly get to the island via a 1-hr. boat trip.

We arrived at the island by 4:50 PM and were assigned our respective de luxe rooms in duplex villas. Jimbo and I stayed at the newly renovated Villa 14-A. Our spacious, tastefully and comfortably decorated airconditioned room had a high ceiling and impressive interiors with 2 very comfortable queen-size beds with many fluffy pillows, a big private bathroom with hot/cold shower and a skylighted ceiling, cable TV with DVD player, a work desk, coffee/tea making facility, sitting area, minibar and a private veranda with lounge chairs. Glasses of the most refreshing lemongrass-calamansi iced tea and a platter of assorted fruits welcomed us inside our room.

Wi-fi is available in our rooms and public areas (pavilion, the pools, some parts of the beach and the lounge areas along the coastline). Lounge areas, with seats and hammocks, are located along the seaside and wooden stairs lead guests to a pocket beach. I’ve nothing but praises for the friendly, courteous and efficiently pro-active staff’s hospitality and their earnest desire to fulfill every request.

Dinner was prepared, al fresco, along the island’s signature shifting sandbar. After this refreshing repast, we made an ocular tour, using an electric tram, of the resort’s 1 and 2-bedroom villas.

These villas feature, aside from the aforementioned de luxe room amenities, a sitting area, a dipping pool and a free-standing bathtub (also a feature in Panglao Bluewater Resort) for the 2-bedroom villa.

Come morning, we had our buffet breakfast at its quiet and lovely, octagonal Island Pavilion restaurant. It offers assorted breads with orange marmalade, strawberry jam and butter spreads; juice (orange or four seasons); fresh milk; hot chocolate, coffee, hash brown potatoes, crispy bacon, omelet, tocino, noodles, etc.

Beside the pavilion is an inviting outdoor infinity swimming pool, overlooking Oslob, with loungers and a breathtaking view of the beach. Just nearby is the resort’s well-stocked bar.

Up ahead was a full day of resort-sponsored activities at Oslob, starting with a 10 min. boat ride to the mainland where we bonded with butanding (whale sharks) and frolicked at Tumalog Waterfalls.

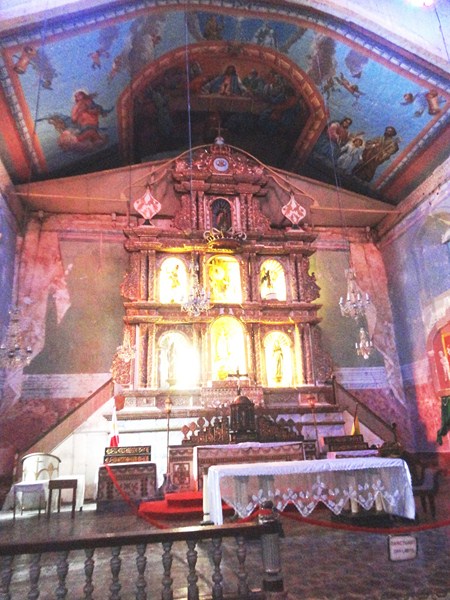

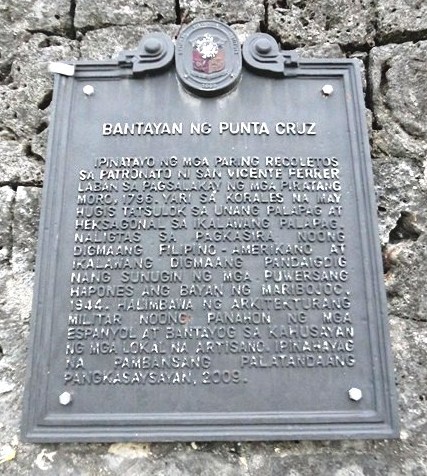

We also reminisced the town’s historical past at the poblacion where we visited the Spanish-era Church of the Immaculate Conception, Cuartel (barracks), baluarte (watchtower), gates and walls. We returned to the resort via a 15-min. boat ride from Bancogon Pavilion and Wharf.

In the afternoon, we all explored the island via a nicely laid out hiking trail, through lush forests, making stopovers at the lighthouse, a Spanish-era baluarte, Yamashita’s Cave and Our Lady of Fatima grotto. Come evening, to refresh their tired bodies, some of the ladies also tried out an outdoor massage at the resort’s Anuma Spa.

On our last day at the resort, Joy and I checked out their 3 glamping tents. Glamping is short for “glamorous camping.” It basically means going camping while trying to make yourself feel that you’re not camping. The tent has all the other features of a regular room such as 2 single beds, carpeted floor, cabinets, lamps, electric fans and a cooler filled with assorted drinks (beer, soda, juice) and chips, all for free. The campsite is located near the beach and the natural lagoon and a bathroom and shower room is close by.

The resort also has a children’s playground, library, dive shop (Aquamania Dive Shop), game room and a souvenir shop. They also offer, airport transfers, 24-hour room service, , kayaking, fish feeding and fishing at the lagoon, Hobie Cat sailing, snorkeling, windsurfing, paddle boating and scuba diving. In the evening, you can join fishermen as they catch krill to feed the butanding the next day.

This highly recommendable resort, an excellent escape from the hustle and bustle of city life and the chaos and stresses of the mind and body, is truly a good place for reflection, prayer, rest, relaxation and romance.

Sumilon Bluewater Island Resort: Brgy. Bancogon, Sumilon Island, Oslob, 6025 Cebu. Tel: (032) 382-0008 and (032) 318-9098. Mobile numbers: (0917) 631-7514 and (0917) 631-7512. Email: info.sumilon@bluewater.com.ph.

Cebu City booking office: CRM Bldg., Escario cor. Molave Sts., Lahug, 6000 Cebu City. Tel: (032) 412-2436. Mobile numbers (0917) 631-7508 and (0998) 962-8263. E-mail: sales.sumilon@bluewater.co.ph.

Manila Office: Rm. 1120, Cityland/Herrera Towers, 98 Herrera cor. Valero St. Salcedo Village, Makati City. Tel: (632) 817-5751 and (632) 887-1348. Fax: (632) 893-5391. E-mail: sumilon@bluewater.com.ph. Website: www.bluewatersumilon.com.ph.