The Galleria Borghese (English: Borghese Gallery), an art gallery housed in the former Villa Borghese Pinciana, houses the largest collection of private art in the world – a substantial part of the Borghese collection of paintings, sculpture and antiquities, begun by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the nephew of Pope Paul V (reign 1605–1621), an early patron of Bernini and an avid collector of works by Caravaggio.

Borghese used it as a villa suburbana, a party villa at the edge of Rome. The collection was originally housed in the cardinal’s residence near St Peter’s but, in the 1620s, he had it transferred to the Casino Borghese, the central building of his new villa just outside Porta Pinciana. Here are some historical trivia regarding the villa:

- The villa was built between 1613 and 1614 by the architectFlaminio Ponzio and Vasanzio, developing sketches by Scipione Borghese himself.

- About 1775, Prince PrinceMarcantonio IV Borghese added much of the lavish Neo-Classical décor. Under the guidance of the architect Antonio Asprucci, the now-outdated tapestry and leather hangings were replaced, the Casina was renovated and the Borghese sculptures and antiquities were restaged in a thematic new ordering that celebrated the Borghese position in Rome.

- In 1808, PrinceCamillo Borghese, Napoleon’s brother-in-law, was forced to sell the Borghese Roman sculptures and antiquities to the Emperor.

- In 1902, the entire Borghese estate and surrounding gardens and parkland were eventually sold to the Italian government.

- The late 18th century rehabilitation of the much-visited villa as a genuinely public museum was the subject of an 2000 exhibition at theGetty Research Institute, Los Angeles, spurred by the Getty’s acquisition of 54 drawings related to the project.

The important collection of paintings by Caravaggio, Raphael and Titian, as well as some sensational sculptures by Bernini and Canova are arranged around 20 decorated rooms over two floors.

The ground floor gallery is mainly dedicated to Classical antiquities of the 1st–3rd centuries AD, Classical and Neo-Classical sculpture, intricate Roman floor mosaics (including a famous 320–30 AD mosaic of gladiators found on the Borghese estate at Torrenova, on the Via Casilina outside Rome, in 1834) and over-the-top frescoes. Its decorative scheme includes a trompe l’oeil ceiling fresco in the first room (or Salone), by the Sicilian artist Mariano Rossi that makes such good use of foreshortening so much so that it appears almost three-dimensional.The upper floor houses the pinacoteca (picture gallery), a snapshot of Renaissance art.

The entrance hall is decorated with 4th-century floor mosaics of fighting gladiators and a 2nd-century Satiro Combattente (Fighting Satyr). High on the wall is the Marco Curzio a Cavallo, a gravity-defying bas-relief, by Pietro Bernini (Gian Lorenzo’s father), of a horse and rider falling into the void.

Antonio Canova’s Venere vincitrice (Victorious Venus or Venus Victrix, 1805–08), a daring depiction of Pauline Bonaparte Borghese, Napoleon’s sister

Sala I is centered on Antonio Canova’s Venere vincitrice (Victorious Venus or Venus Victrix, 1805–08), a daring depiction of Pauline Bonaparte Borghese, Napoleon’s sister, reclining topless. It is the most famous piece in the museum and virtually its symbol.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini‘s spectacular output of secular sculpture of flamboyant depictions of pagan myths also steal the show. In the swirling Apollo e Dafne (Apollo and Daphne, 1622–25, created by Bernini at the tender age of 24 for the Scipione Borghese) in Sala III, Daphne’s hands morph into leaves, while in the dynamic Ratto di Proserpina (Rape of Proserpine, 1621–22) in Sala IV, Pluto’s hand presses into the seemingly soft flesh of Persephone’s thigh.

All are considered seminal works of Baroque sculpture. Other works include Goat Amalthea with Infant Jupiter and Faun (1615), David (1623) and Aeneas, Anchises & Ascanius (1618–19).

Sala VIII (Sala de Sileno) is dominated by works by Caravaggio including the dissipated-looking Bacchino Malato (Young Sick Bacchus; 1592–95), the strangely beautiful La Madonna dei Palafenieri (Madonna with Serpent; 1605–06) and San Giovanni Battista (St John the Baptist; 1609–10), probably Caravaggio’s last work.

There’s also the much-loved Ragazzo col Canestro di Frutta (Boy with a Basket of Fruit, 1593–95), St Jerome Writing (1606), and the dramatic Davide con la Testa di Golia (David with the Head of Goliath; 1609–10, Goliath’s severed head is said to be a self-portrait sent to the Pope to beg for forgiveness after Caravaggio was accused of murder).

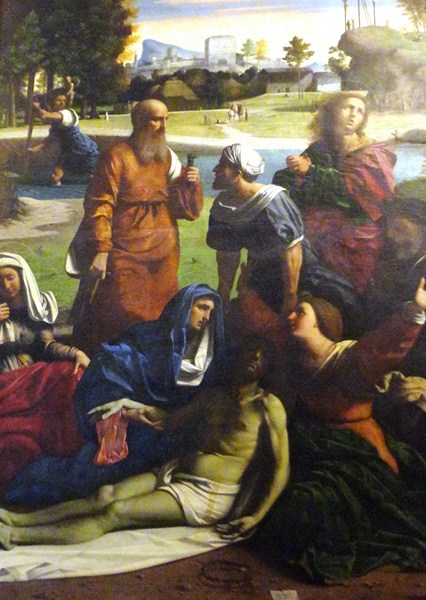

Upstairs, the pinacoteca displays Raphael’s extraordinary La Deposizione di Cristo (Entombment of Christ, 1507) in Sala IX, and his Dama con Liocorno (Lady with a Unicorn; 1506). In the same room is Fra Bartolomeo’s superb Adorazione del Bambino (Adoration of the Christ Child; 1495) and Perugino’s Madonna con Bambino (Madonna and Child; first quarter of the 16th century).

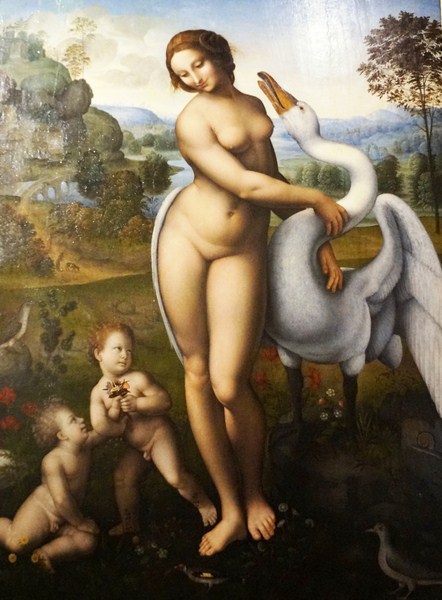

Other highlights include Correggio’s erotic Danae (1530–31) in Sala X, Bernini’s self-portraits in Sala XIV, and Titian‘s early masterpiece, Amor Sacro e Amor Profano (Sacred and Profane Love; 1514) in Sala XX.

There are also works by Peter Paul Rubens and Federico Barocci. In addition, several portrait busts are included in the gallery, including one of Pope Paul V, and two portraits of Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1632, the second portrait was produced after the a large crack was discovered in the marble of the first version during its creation).

Borghese Gallery: Piazzale del Museo Borghese, 5, 00197 Rome, Italy. Tel: +39 06 841 3979 and +39 06 32810. Open Mondays to Fridays, 9 AM – 6 PM, Saturdays, 9 AM – 1 PM. Website: www.galleriaborghese.it. Admission: € 11.00. To limit numbers, visitors are admitted at two-hourly intervals, so you’ll need to pre-book your ticket and get an entry time.

How to Get There: Pinciana- Museo Borghese (Bus 52, 53, 83, 92, 217, 360, 910)