From the Church of the Holy Cross in Tanza, Jandy and I next drove the long 21.6 kms. distance to the Diocesan Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Naic. First constructed in the 1800s with wood and cogon grass, six years after its initial construction, a kopa, a pair of cruets and ornamentation was added. In 1835, the construction of a new stone church was started by Don Pedro Florentino. Its bell tower was completed in 1892.

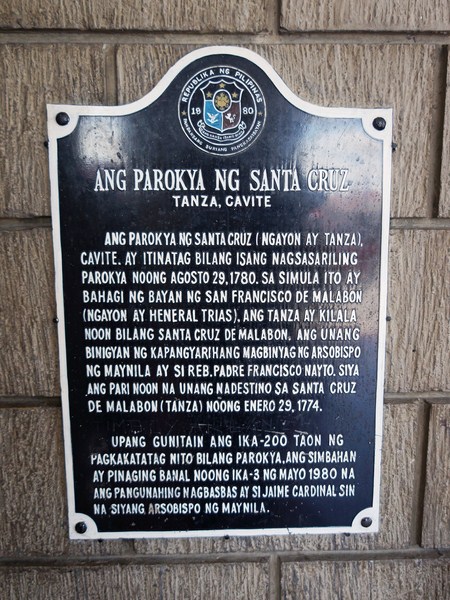

Check out “VIsita Iglesia 2017” and “Church of the Holy Cross“

After the Tejeros Convention of March 22, 1897, the the church convent was used as the headquarters of Andres Bonifacio and the Naic Conference was held there. In this conference, the old Tagalog letter of the flag was replaced by the “Sun of Liberty,” with two eyes, a nose and a mouth and its symbolic eight rays.

Before World War II, the church was one of the tallest (about 5 storeys high) and the longest (almost 10 blocks long) churches in Cavite. In width, it was second to the Imus Cathedral. On November 17, 1996, it was made into a Diocesan Shrine.

AUTHOR’S NOTES:

The church’s three-level Neo-Gothic façade, the only one of its kind in Cavite, has a pointed, lancet-like arched main entrance flanked by square pilasters and similarly pointed arched windows.

The second level has three pointed arched windows while the triangular pediment, with inverted traceries below the eaves, has a circular window at the tympanum. The central pilasters rise up to the pediment and end up in pinnacles, dividing the façade into 3 vertical sections. The sides of the church are reinforced by thick buttresses.

The 4-storey, square bell tower, on the church’s left, has alternating circular and pointed arched windows and is topped by a pyramidal roof.

Its interior has 3 major and 2 minor Gothic-style altars with the Very Venerated Image of the Immaculate Concepcion, Patron Lady of Naic, in the main altar.

Diocesan Shrine of the Immaculate Conception: Capt. Ciriaco Nazareno St., Poblacion, Naic 4110, Cavite. Tel: (046) 412-0456. Feast of the Immaculate Conception: December 8.

How to Get There: Naic is located 47 kms. from Manila, 13.3 kms. from Trece Martires City, 12.9 kms. from Maragondon and 12.8 kms. from Tanza.