|

| The Sto. Entierro |

Visita Iglesia (Tayabas and Lucban, Quezon)

Today being Good Friday, Jandy and I also joined Jun and Jane’s relatives for the visita iglesia, the traditional visit to 7 churches. We motored to the nearby town of Tayabas, just 23 kms. from Sariaya, and dropped by the St. Michael the Archangel Minor Basilica were we recited the 14 Stations of the Cross. The longest Spanish colonial church in the country and also one of the oldest, this 103-m. long church was first built by the Franciscans in 1585, repaired in 1590 by Pedro Bautista, changed into brick in 1600, destroyed by an earthquake in 1743 and later rebuilt and enlarged in 1856 by building a transept and cupola. The church’s roof was changed to galvanized sheets in 1894 and its belfry contains an 18th century clock, the only one of its kind in the country, that chimes every 30 minutes. It was made into a minor basilica on October 18, 1988 and has an antique organ, a balcony over the altar and a now unused tunnel from the altar.

| St. Michael the Archangel Minor Basilica |

| Church of San Luis Obispo de Tolosa |

Church of St. Francis of Assisi (Sariaya, Quezon)

We next walked towards the town’s church and plaza. A typical Spanish town, the town’s church (St. Francis of Assisi) and the municipal hall all face the plaza. The plaza has a circular patio flanked by a row of 8 torch-bearing statues of the Muses of Liberty as well as a statue of our National Hero, Dr. Jose P. Rizal, inaugurated on December 30, 1924.

| Church of St. Francis of Assisi |

The Ancestral Houses of Sariaya (Quezon)

The next day, Good Friday, Jandy and I explored the town’s ancestral houses in detail, bringing along my point and shoot camera and videocam. Sariaya is known for its ornate and imposing American-era mansions built by illustrados (landed gentry) like the Cabunags, Enriquez, Gala, Luna, Obordos, Ramas and Rodriguez clans, all coconut planters who once grew rich from 1919-30 from the once profitable coconut industry. In 1945, the town was set afire by Japanese troops, destroying many of its stately ancestral homes. A big fire also occurred in the 1960s.

|

| Dona Margarita Rodriguez Ancestral House |

The burnt-out shells of these homes can still be seen around town. Surviving ancestral homes are scattered around the town plaza and along Rizal St., perpendicular to the highway. They create a beautiful and nostalgic setting that reflects the town’s illustrious past. Beside the house we stayed in is the old, and equally stately, ancestral home owned by Jun’s grandmother, the late Dona Margarita Rodriguez, an old maid who died in the 1950s.

The Rodriguez Ancestral House (Sariaya, Quezon)

Prior to Holy Week, I got an invitation from Celso “Jun” and Jane Segismundo, my friends from Couples For Christ, to join them and Jane’s relatives to visit Jun’s ancestral home in Sariaya, Quezon. For company, I decided to bring along my son Jandy. Our convoy of cars departed 1:30 AM, Holy Thursday (April 1) to avoid the Holy Week rush. It was an uneventful, leisurely but very rainy (unusual for Holy Week) 2.5-hr. (124.64-km.) trip (including 2 stops) via the South Luzon Expressway (SLEX) up to its terminus (Calamba City), then passing by Mt. Makiling, Sto. Tomas and Tanauan City in Batangas, Alaminos and San Pablo City in Laguna and then Tiaong and Candelaria in Quezon. We arrived at the town by 4 AM.

|

| Rodriguez Ancestral House |

Sariaya is located 1,200 ft. above sea level near the foothills of 2,177-m. high Mt. Banahaw, an active volcano shrouded in legend and mysticism. The town’s name was derived from Sadiaia, the former name of the Lagnas River.

|

| The second floor sala (living room) |

The house that we stayed in was featured inside brochures concerning Quezon province and in pages 138-141 of the book “Philippine Ancestral Homes” by Fernando N. Zilacita and Martin I. Tinio, Jr.. Newly restored, it was built during the Spanish era by Jun’s maternal ancestors, the Rodriguez’s. The house was enlarged in the 1920s and was partially burned during the Japanese rampage. It had about 7 huge bedrooms, a huge second floor sala, an equally spacious dining room and kitchen and quarters for the caretakers. Like most houses made during that era, it has a grand stairway, tall doors, high ceilings (even inside the bathrooms), antique period furniture, huge stained glass and capiz windows, verandillas, narra plank flooring and wall paintings.

Upon our arrival, Jandy and I opted to sleep at the mansion’s ground floor bedroom (1 of 4). It had its own lavatory and a silohiya bed which didn’t actually fit my 5′-10″ frame. I found out later that it was for the children’s bedroom. For reasons I never bothered to ask, all the others slept together at the second floor sala. Fear of ghosts maybe?

A Day Tour of Batad Rice Terraces (Banaue, Ifugao)

|

| Batad Rice Terraces |

A stay in Banaue is never complete without visiting the Batad Rice Terraces. Seeing it is a “must” but getting there is no picnic as I was soon to find out. The next day, April 12, Easter Sunday, after an early morning breakfast at the inn, Jandy and I were joined by Asia, Min-Min and Tom as we proceeded to the Trade Center. Here, we hired a jeepney for PhP1,500 and waited awhile for other hikers to join us, our intention being to split the bill even further. There were no takers. We decided for the 5 of us to go at it alone. The Batad Rice Terraces are located 16 kms. from the town and 12 kms. of the distance can be traversed, over the dusty Mayoyao national road, by our jeepney. Luckily for us, there were no sudden occurrences of landslides triggered by too much heat, it being the peak of the El Nino season. We safely made it all the way to the junction at Km. 12.

From hereon it would be hiking for the rest of the 4-km. distance. Jandy and I had on our indispensable media jackets (with its many pockets) and I brought along bottled water and my Canon point and shoot camera and videocam. The 2 to 3-hr. uphill/downhill and winding hike is demanding, but rewarding for hardy and seasoned hikers in good physical condition. I didn’t exactly fit in that category as I wasn’t in good shape. Jandy, a specimen of good health, kept egging me on – as I was huffing, puffing and sweating profusedly (even in the cold mountain air) – so I could keep up with the group, being the frequent tailender. Luckily, for me, there were about 6 waiting sheds offering refreshments (as well as souvenir items) to hikers. The rugged mountain trail sometimes narrowed to footpaths where only one person at a time could pass. Below us were treacherous ravines. Fog sometimes blanketed these trails.

After a few hours we emerged at the Batad “Saddle” in Bohr-Bohr, a landmark station in Cordilleras used to gauge the distance stretching to Batad. After another arduous hike, we finally reached our destination – the Simon Inn Viewpoint and its breathtaking side vistas of the Batad Rice Terraces. This stupendous amphitheater of stone and earth terraces, sculpted out of twin coalescing spurs of a steep, wooded mountain from riverbed to summit, are considered as the “Eighth Wonder of the World” and, unlike the more famous Pyramids of Egypt built by slave labor, were built in the true bayanihan spirit (system of helping each other without fees). However, the rice terraces weren’t as green as I would have wanted them to be, again it being the height of the El Nino phenomenon.

Below the viewpoint and adjacent to the rice terraces is Cambulo Village, a typical, unspoilt Ifugao village with two lodges and pale Hershey Kisses-like roofs in the midst of terraces. My 3 companions decided to visit this rustic cobblestoned village where the ancient craft of bark cloth weaving thrives. Going down seemed easy but I dreaded the uphill return trip so I opted to stay behind and admire the view instead. Too bad I didn’t bring any extra clothes with me. It would have been nice to have stayed overnight. Maybe next time. My 3 companions returned after 2 hrs.. After a 3-hr. stay (including lunch at the inn), we retrace our way back, under a more comfortable late-afternoon sun, to the Km. 12 junction where our jeepney waited for us. Unlike our previous trip, our jeepney was now filled to capacity with foreign and local hitchhikers all thankful for the free ride back to town. They then left us to settle our bill with our driver. The nerve!!! Jandy and I then proceeded to the Autobus ticket office at the town center to reserve bus seats as there was only one trip back to Manila. Asia, Min-Min and Tom planned to spend an extra day in Banaue. Afterwards, we returned to People’s Lodge for a well-deserved dinner and rest.

The next day (Monday), after a very early breakfast at the inn, we proceeded to the Trade Center where we boarded our Autobus bus for the 347-km. (10-hr.) long-haul trip back to Manila via the Dalton Pass in Nueva Vizcaya. Although the bus was branded as “aircon,” it would have been better for us to open the bus windows as the airconditioning wasn’t working. It was hot all the way. However, as soon as we reached the lowlands, my mobile phone became useful again. Thank God.

People’s Lodge & Restaurant (Banaue, Ifugao)

|

| People’s Lodge & Restaurant |

It was getting late and we had to find lodgings by nightfall. After a short but tiring uphill search at the town center, we decided to stay at the People’s Lodge & Restaurant, a pension house, where we took 1 of its 15 double rooms with common bath for PhP100 per head. Quite cheap. The inn also had 6 double rooms with bath, a bakery, restaurant and an all-important telephone.

|

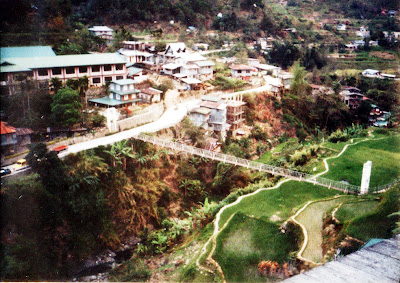

| Viewof the Ibulao River from our inn. |

Ever since we left Baguio City, my cellular phone just became useless baggage and I took the opportunity to make a long distance call to my wife Grace who hasn’t heard from us for 5 days. From its restaurant, we had a beautiful view of the town, the banks of the scenic Ibulao River (traversed by a hanging steel footbridge) and a backdrop of rice terraces. Coincidentally, Asia, Min-Min and Tom also happened to be staying here and, together, we made plans for a joint early morning trek to the Batad Rice Terraces. After an early dinner and a very very cold shower, Jandy and I retired for the night.

People’s Lodge & Restaurant: Banaue-Mayoyao-Potia-Isabela Rd., Banaue, Ifugao. Tel: (074) 386-4014 to 15.

Arrival in Banaue (Ifugao)

The 47-km. jeepney ride from Bontoc to Banaue, Ifugao province’s main tourism destination, was to take all of 2.5 hrs., the seemingly short distance made while climbing steep mountains via the dusty, narrow and bumpy Halsema Highway. The discomfort was somehow alleviated by great views of some rice terraces that we passed. By 4 PM, we arrived at the parking area for buses and jeepneys at the town’s Trade Center. Banaue is the province’s transportation hub, being traversed by the one major highway leading south to Nueva Vizcaya and Manila and by a less-developed road going to Bontoc (Mountain Province), and from there, to Baguio City (Benguet).

|

| Banaue town |

This touristy area is the center of activity in the town and it has handicraft shops selling different kinds of traditional fabric like the woven bark cloth and dyed ikat cloth, wooden objets d’art such as bowls, trays, oversized spoons and forks, antiques, entirely alien statues of American Indian chiefs and smiling, pot-bellied Chinese gods, and the traditional bul-ols (statues of rice gods). Curio souvenirs include handwoven wall hangings, crocheted bedroom slippers and pfu-ong (traditional jewelry) representing good luck in hunting or prosperity of children. At one end of it is the Municipal Hall and Post Office Sub-station.

Stopover at Bontoc (Ifugao)

|

| Bontoc Village Museum |

After a 4-day stay in Sagada, Jandy and I left in a jeepney bound for Bontoc, the Ifugao provincial capital, early in the morning of April 11, Black Saturday. The 18-km. trip took all of an hour and we arrived at the provincial capital’s municipal plaza by 11 AM. From here, we were to take another jeepney bound for Banaue (Ifugao). The 396.1 sq. km. Bontoc, the biggest town in the Cordillera heartland and the Bontoc Igorot’s cultural center, lies 3,000 ft. above sea level in a trough formed by the eastern and central ranges of the Cordillera mountains in the Chico Valley.

|

| With curator Sister Teresita Nieves Valdes |

We still had time to spare before the jeepney leaves for Banaue, so we did some sightseeing. We walked to nearby Catholic ICM Sisters’ convent and the St. Vincent’s Elementary School and visited the Bontoc Village Museum. Also called the Ganduyan Museum, it was established by Mother Basil Gekiere and run by the Belgian ICM missionaries. The museum presents a good overview of the differences and similarities between the mountain tribes (Bontoc, Kalinga, Kankanai and Tingguian and the Gaddang, Isneg and Ibaloi of the Ifugao).

|

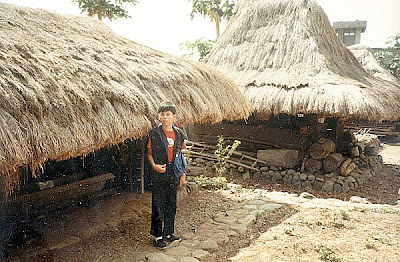

| Jandy at the outdoor museum |

Its 4 well-laid out and labeled rooms features artifacts (woven fish traps, death chair, head basket, ceremonial bowls, ritual backpack, etc.), musical instruments (jew’s harp, zither, flute, etc.), a group of miniature traditional houses, a collection of rocks and fossils from different parts of the Cordilleras and interesting old photos of the Bontocs’ colorful pre-Christian history, including some early 1900s photos of their headhunting days (one shows a beheaded person tied up in a bamboo pole and, another, a burial for such a beheaded person). At the basement is a library with a limited collection of books. There is also a carved wooden chest to put a curse on people and a basket where a chick is placed to awaken the spirits with its constant chirping. Its museum shop sells postcards, carved wood items and other novelties. I, being a postcard collector, bought a sepia-colored postcard pack of 6 featuring pictures of the museum artifacts. I also got to interview Sister Teresita Nieves Valdes, the museum curator.

|

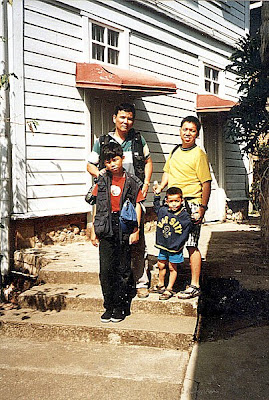

| Banny and me with our sons |

We also visited the adjacent outdoor museum with its full-scale model of a traditional Bontoc village including the ulog for maidens and a pit shelter for swine. On my way out I met my former officemate (Manosa-Zialcita Architects) Jose Bayani “Banny” Hermanos who was also travelling with his wife Carol and two sons. An avid traveler like me, he is also a professional photographer whose colored photos were featured in The Philippines: Action Asia Adventure Travel Guide. After our museum visit, we proceeded to the nearby Pines Hotel & Kitchenette for a quick lunch. Then, we went back to the municipal plaza where we boarded the last Banaue-bound jeepney. Here, I befriended sisters Asia and Min-Min, one of which was traveling with her German boyfriend named Tom. We left Bontoc by 1:30 PM.

Good Friday in Sagada (Mountain Province)

Good Friday, our last whole day in Sagada, was partly spent in prayer. Together with my Danum Lake companions who were also staying in my inn, we made our way past the school gate and up some steps to the cemetery where Eduardo Masferre, the famous photographer (June 24, 1995), and William Henry Scott (1993), are buried. It has a view of the northern valley. Further up is Calvary, the highest point in the town cemetery which is marked with a huge cross. Here, we visited and prayed at its 14 Stations of the Cross.

|

| Sagada Cemetery |

From the cemetery, a steep path took us to Echo Valley. Halfway down, we viewed hanging coffins on large, gray limestone cliffs at the opposite side and some small burial caves. There are still a few sangadil (“death chairs”) next to the hanging coffins, placed there for the spirits to rest on.

|

| Hanging coffins |

When a Sagadan nears old age, he is given the choice of cave burial or “hanging coffins.” The deceased is cladded in special burial attire woven by a widow in the village. This ensures that the spirit (anito) community would recognize them and admit them to the spirit world.

They are bound to a sangadil (death chair) and placed on the house porch for the duration of the long makibaya-o (wake period). During the makibaya-o, pigs are sacrificed, dirges are sung and eulogies given during the all-night vigils.

The empty coffin is first taken to the burial site (cave or rock ledges). The funeral procession follows later, preceded by torchbearers who make sure that no animals crosses its path. When bad omens are encountered, the previously selected burial site could be changed at the last moment in the belief that the new arrival is not welcomed by the present occupants.

The deceased’s body is borne by young lads who vie with one another for the honor of carrying it the furthest distance. In doing so, it is believed that he would gain much strength and wisdom from the deceased. Today, these traditional rites are still being practiced, although on a smaller or revised scale, and still requested by some old people.

However, most are now buried on family land or at the Christian cemetery. The makibaya-o, whether traditional, Christian or in combination, is still significant in adult deaths.

The next day, Saturday, after breakfast at the inn, Jandy and I left Sagada on the 10 AM jeepney bound for Bontoc.