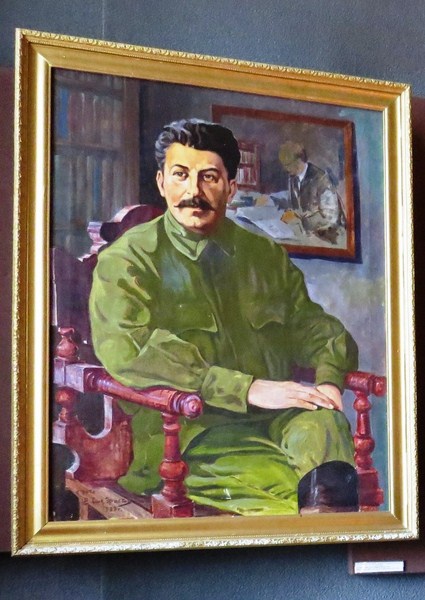

We were already through with the first day of our 3-day GNTA-sponsored tour of the Georgia countryside, our last destination being the Stalin State Museum in Gori. We still had a lot of daylight left, so we decided to continue on to the ancient, rock-hewn and now abandoned town of Uplistsikhe (literally meaning “the lord’s fortress”), located in Shida Kartli, a suburb just 14 kms. (a 20-min. drive) east of Gori.

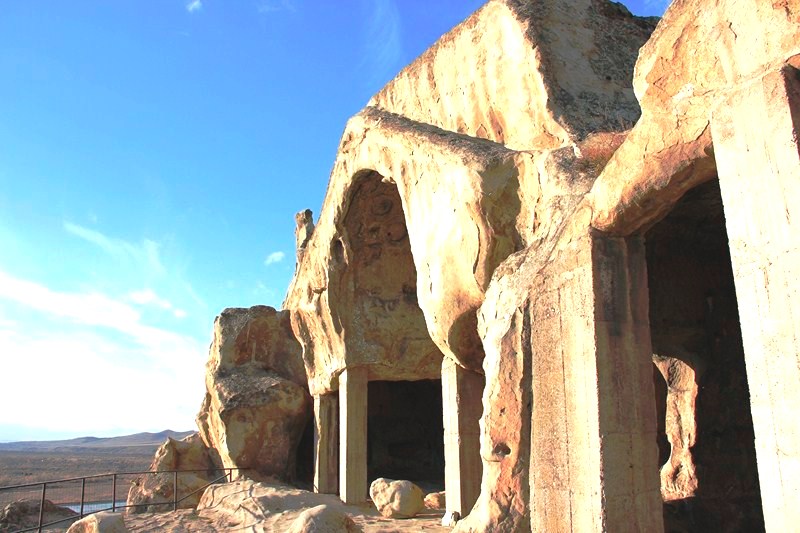

Uplistsikhe is remarkable for the unique combination of various styles from rock-cut cultures of the region, most notably from Cappadocia in Anatolia (now modern Turkey) and Northern Iran, and the co-existence of pagan and Christian architecture. Built on the high rocky sandstone massif along the left bank of the Mtkvari River, the area was identified by archaeologists as one of the oldest urban settlements in Georgia, containing various structures dating from its founding in the Late Bronze Age (around 1,000 BC) to the Late Middle Ages (13th century AD). Its natural sandstone rock easily lent itself to various kinds of treatment, making it possible to create complex decorative compositions.

Strategically located in the heartland of ancient kingdom of Kartli (or Iberia as it was known to the Classical authors), the town’s age and importance as a major political and religious center of the country (between the 6th century BC and the 11th century AD) led medieval Georgian written tradition to ascribe its foundation to the mythical Uplos, son of Mtskhetos, and grandson of Kartlos.

Early in the 4th century, with the Christianization of Kartli, Uplistsikhe seems to have declined in its importance, losing its position to Mtskheta and, later, to Tbilisi, new centers of Christian culture. During the Muslim conquest of Tbilisi in the 8th and 9th century, Uplistsikhe reemerged as a principal Georgian stronghold, becoming the residence of the kings of Kartli, during which the town grew to a size of around 20,000 people and evolved into an important caravan trading post along the Silk Road. However, a Mongol raid in 1240 destroyed large parts of the town, marking the ultimate eclipse of the town. It was virtually abandoned and, only occasionally, in times of foreign intrusions, used as a temporary shelter.

The approximately 4-hectare Uplistsikhe complex, tentatively divided into 3 parts, consists of a south (lower), middle (the largest) and north (upper) part. The middle part, containing the bulk of Uplistsikhe’s rock-cut structures, is connected to the southern part via a narrow rock-cut pass and a tunnel. Narrow alleys and, sometimes, staircases radiate from the central “street” to the different structures.

Most of the caves are devoid of any decorations. However, some of the larger structures have coffered, tunnel-vaulted ceilings, with stone carved in imitation of logs, as well as niches, which may have been used for ceremonial purposes, in the back or sides. Archaeological excavations in the area since 1957 (when only the tops of a few caves were visible) have uncovered numerous artifacts from different periods, many of which are in the safekeeping of the National Museum in Tbilisi. Most of the unearthed artifacts include gold, silver and bronze jewelry, plus samples of ceramics and sculptures.

The earthquake in 1920 completely destroyed several parts of the most vulnerable areas and the stability of the monument remains under substantial threat, prompting the Fund of Cultural Heritage of Georgia, a joint project of the World Bank and Government of Georgia, to launch a limited program of conservation in 2000. Since 2007, the Uplistsikhe cave complex has been on the tentative list for inclusion into the UNESCO World Heritage program. Originally, the city had about 700 caves but, today, only 150 remain.

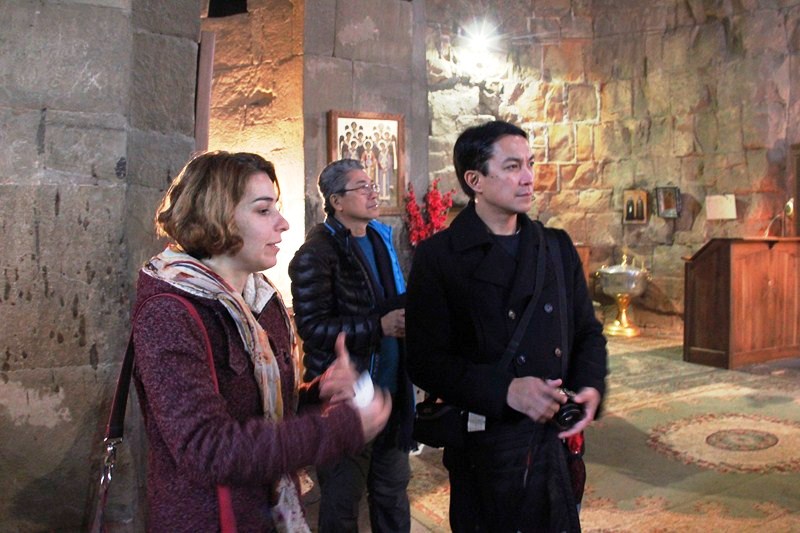

We all arrived at Uplistsikhe at around 4 PM, paid the entrance fee and started our 2-hour exploration of the 40,000 sq. m. Shida Qalaqi (“Inner City”), which is less than half of the original whole, by hiking about 5 m. up the rocks (opposite the toilets and cafe at the entrance), then following the rock-cut path to the left. Steps, with metal railings, lead us up through what was the main gate. To the right, sitting under a corrugated roof, is the excavated main tower of the Shida Qalaqi’s defensive walls.

We observed many round pits dug in rock, thought to have been used for corn storage or for sacrificial purposes, while tadpole-shaped pits may have been ovens used for baking bread. Scattered throughout the city are narrow circular holes, of different depths, cut in the ground to hold several prisoners.

We also noticed a wine cellar, a pool for water storage and a wine press where grapes are crushed, allowing the juice to run down a chute into another container. During the hike, we made short stops in between to admire the beautiful view of the river and the whole surroundings.

Ahead of us, overlooking the Mtkvari River, is the Theateron (Theater), probably a temple from the 1st or 2nd century AD where religious mystery plays may have been performed. This cave has a pointed arch, carved in the rock above it, and an ornate, tunnel-vaulted ceiling carved with octagonal Roman-style designs resembling three-dimensional plaster work. Behind the stage are dressing rooms.

Returning towards the main gate, we turned left to wind your way up the main street. Down to the right is the large pre-Christian Temple of Makvliani. With an inner recess behind an arched portico, the open hall in front has stone seats for priests.

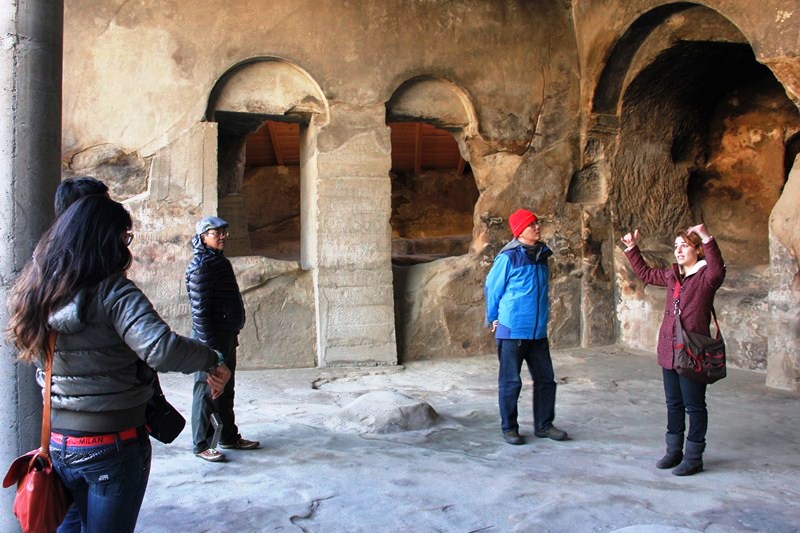

A little further up, on the left, is the big hall known as Tamaris Darbazi (Hall of Queen Tamar), almost certainly a pagan temple (though Georgia’s great Christian Queen Tamar may have used it later). Behind two columns cut from the rock is a stone seat dating from antiquity. The hall has loggias on three sides. The ribbed stone ceiling, cut to look like wooden beams, has a hole to let smoke out and light in. An open area, to its left, has stone niches along one side, thought to have once been a pharmacy or dovecote. To the right of Tamaris Darbazi is a large cave building, probably a pagan sun temple used for animal sacrifices and, later, converted into a 3-naved Christian basilica.

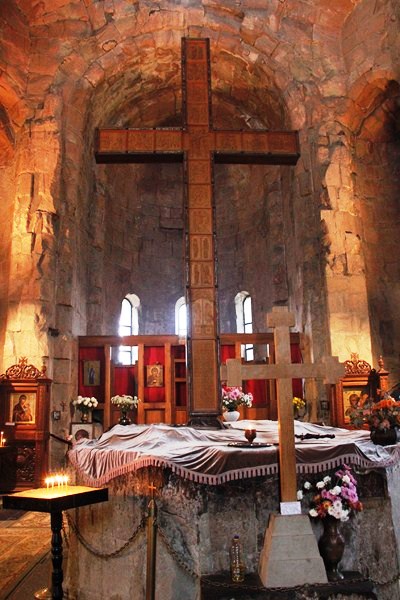

Near the summit of the hill is the Uplistsulis Eklesia (Prince’s Church), a picturesque triple-church Christian basilica built with stone and brick in the 9th -10th centuries over what was probably Upliistsikhe’s most important pagan temple. Inside the simple interior are some candlelit icons but no frescoes (they have been whitewashed).

Outside, we again had breathtaking views of the river and the Caucasus Mountains. On our way back, we entered a dark, 40 m. long tunnel with a long flight of metal stairs, behind a reconstructed wall beside the old main gate, running down to the Mtkvari River, an emergency escape route that could also have been used for carrying water up to the city.

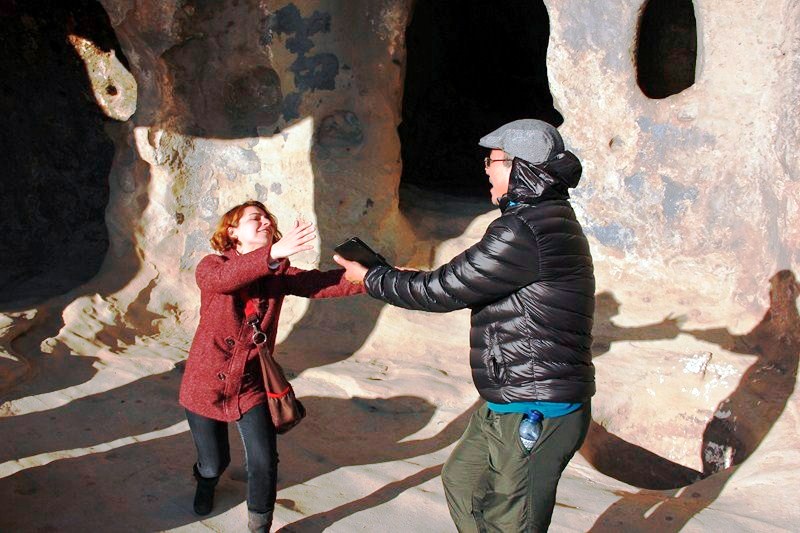

Our visit to this lovely place with an interesting history was unique in that we really had full access to the whole site (elsewhere most of this would all be fenced off) so we really got the feel of this city literally cut into the mountainside by soaking up its history and rustic charm. Well off the beaten track, but definitely worth a visit. The memory of this lovely ancient cave city would linger in my mind long after I have gone home.

Uplistsikhe: Shida Kartli, Gori, Georgia. Open 11 AM – 6 PM. Admission: 3 GEL.

Qatar Airways has daily flights from Diosdado Macapagal International Airport (Clark, Pampanga) to Tbilisi (Republic of Georgia) with stopovers at Hamad International Airport (Doha, Qatar, 15 hrs.) and Heydar Aliyev International Airport (Baku, Azerbaijan, 1 hr.). Website: www.qatarairways.com.