Part 3 of the Bluewater Maribago Beach Resort & Spa-sponsored City Tour

The grandiose Temple of Leah, Cebu City’s newest attraction, has been called the “Taj Mahal of Cebu.” Perched on the hilltop of Busay, it was built by Teodorico Soriano Adarna, owner of the Queensland chain of motels in Davao, Manila and Cebu, as a testament to his undying love and ceaseless devotion for Leah Villa Albino-Adarna, his wife of 54 years (Leah was 16 and Teodorico was 19 when they married), who died of lung cancer in 2012 at age of 69.

They had four children— the 56 year old Allan, 54 year old Arlene, Arthur (deceased) and the 39 year old Alex, plus 16 grandchildren, including 29 year old Filipina actress and model Ellen Adarna (eldest and only daughter of Allan). Teodorico has since remarried and now lives in Davao.

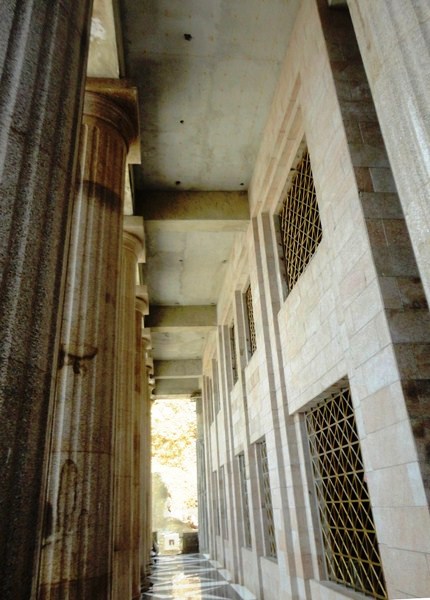

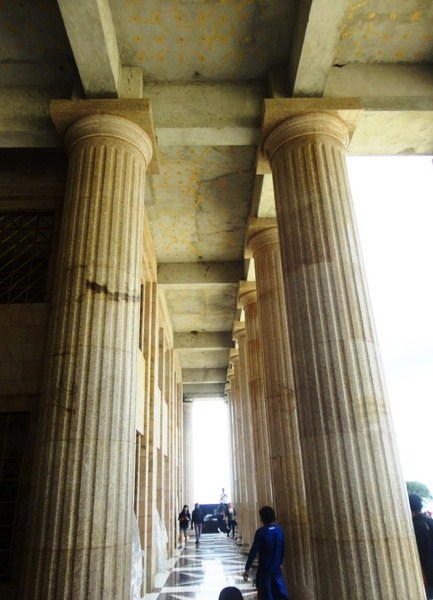

This 7-storey, still unfinished temple became an instant domestic tourist attraction as it interestingly resembles the ancient Parthenon of Greece. Started in 2013, this Philippine version of the Taj Mahal of India is due to be completed in 2020. The west balcony, surrounded by resplendent sculptures along the balustrade, has a panoramic view of the cities of Metro Cebu (Cebu, Mandaue and Lapu-Lapu) and Cebu City’s highlands.

Its fountain has statues of four seated horses at the base and three naked maidens (in my opinion, they are probably The Three Graces) standing on a basin on top that were inspired by the Adarnas’ trip to Europe.

The Classic Greek and Roman-inspired (rectangular design, raised podium for the shrine, a triangular pediment above the portico of fluted Doric columns and an altar of the cult goddess under the skylight) architecture of this huge edifice is meant to be admired from the outside, awing visitors with its imposing breadth. The engraved moldings on the vaulted ceiling were, on the other hand, inspired by the temples of India.

Inside are 24 chambers, built on opposite wings, including a museum, an art gallery and a library with all the favorite and personal belongings of Leah such as books, vases, Buddha heads and various figurines, ceramic statues and souvenirs gathered from the couple’s extensive travels.

The statues of gigantic seated lions, on each side of the grand staircase, guided us to the door step of another jaw-dropping view, at the middle of the temple, of a grand Y-shaped staircase, a pair of huge brass angels and the 9-ft. high, bronze statue (said to have cost PhP4,000,000) of a seated Leah Albino-Adarna on a marble pedestal, with crown and flower.

Behind the statue is a semicircular arched stained glass window featuring various angels. At the foot of the statue is this inscription:

BELOVED WIFE AND MOTHER

Leah V. Albino-Adarna was chosen Matron Queen of her Alma Mater, the University of Southern Philippines. This nine-foot bronze statue portrays her composure and regal bearing when she was crowned. May the beholder discern her innate beauty, poise and genteelness.

(signed)

Teodorico Soriano Adarna

Born December 13, 1938

Temple of Leah: Roosevelt St., Brgy. Busay Cebu City. Tel: (032) 233-5032. Mobile number: (0906) 324-5687. Open daily, 6 AM – 11 PM. Admission: PhP50 per pax. Professional photography for events: PhP2,500. Parking fee: PhP100 if inside the premises, free if outside (limited slots only).

Bluewater Maribago Beach Resort & Spa: Buyong, Maribago, Lapu-Lapu City, 6015, Cebu. Tel: (032) 492-0100. Fax: (032) 492-1808. E-mail: maribago@bluewater.com.ph. Website: www.bluewatermaribago.com.ph. Metro Manila sales office: Rm. 704, Cityland Herrera Tower, 98 Herrera cor. Valero Sts., Salcedo Village, Makati City, Metro Manila. Tel: (02) 887-1348 and (02) 817-5751. Fax: (02) 893-5391.

How to Get There: From JY Square, ride a jeepney going to Busay (PhP10, one-way) and ask to be dropped off at the mountain view highway intersection. From there, you can walk towards the Temple of Leah. From JY Square, you can also hire a habal-habal (motorcycle) going to the Temple of Leah. Fare is about PhP50-100. For a more convenient ride, you can just hail a cab.